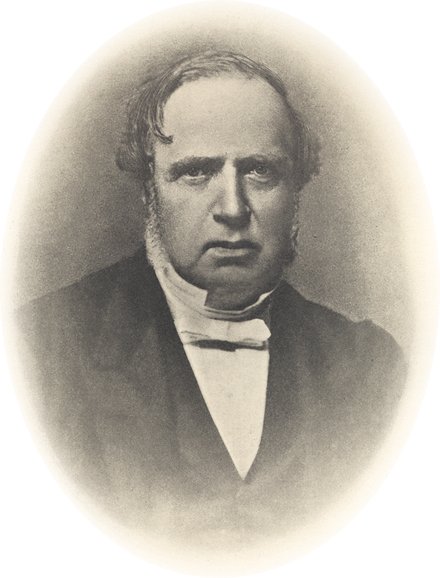

Born in Glasgow on 27 September 1805, Blackie entered the family bookselling and publishing business. From 1831, the firm became known as Blackie & Son, publishing annotated editions of the Bible and establishing the Scottish Guardian. This, the earliest religious newspaper published in Scotland, ran from 1832-1862 and was regarded as Liberal in politics and evangelical in religious matters.

In 1857 Blackie was elected on to the Glasgow council, and in 1863 became Lord Provost. He proposed the City Improvement Scheme, a major plan to improve the quality of life in the poorer areas. He was also involved in bringing water to the city from Loch Katrine.

In 1859 he was made a magistrate of the burgh, and was also an elder of the Free Church. He died on 12 February 1873 following an attack of pleurisy, leaving a widow, Agnes (they had married in 1849), and three sons.

FOR many of her most prominent citizens, Glasgow has been deeply indebted to neighbouring country towns and parishes; but Mr. Blackie was thoroughly a Glasgow man. He was born there on 27th September, 1805. His father, John Blackie, senior, and his mother, Catherine Duncan, were also natives of the city. He was the eldest child of a family of eight, of whom two still survive.

Young Blackie was sent to the then well-known school of Mr. William Angus,(1) who was considered the best teacher of English in the town. Afterwards he passed on to the High School where he made good progress under Mr. Gibson. In commercial arithmetic, in which he became very expert, his teacher was Mr. Thomas Rennie, who in his own department enjoyed the highest reputation, and is still held in grateful recollection by many who profited by the shrewd methods he adopted for training his pupils.

His mother's relations were resident in Bute; in his early days he frequently visited them. This was before the time of railways or steamboats. The mode of conveyance then was by flyboat to Greenock, and thence by smack to Rothesay - a trip which usually occupied two or more days. On one occasion, being favoured with a good tide in the river, and the opportune departure of the smack soon after his arrival in Greenock, he reached Rothesay on the evening of the day on which he started. But so unheard of was such expedition, that the good people of Rothesay would not for a time credit the fact that he had only left Glasgow that morning. Their incredulity was not to be wondered at, seeing that his mother had on one occasion taken eight days to accomplish this journey, which can now be made in an hour and a half.

After leaving school, young Blackie joined the bookselling and publishing business commenced by his father in 1809, and at this time carried on under the firm of William Sommerville, Archibald Fullarton, J. Blackie, & Co. In 1826 the style of the firm was changed to that of Blackie, Fullarton, & Co., and Mr. Blackie, junior, being now twenty-one, was admitted a partner. For this position he was admirably qualified by his methodical habits and his literary tastes. From this time till his death, the publications of the firm were produced mainly under his guidance, and his influence everywhere was soon made manifest. More especially was this the case subsequent to 1831, in which year Mr. Blackie and his father became the sole partners in the business which has since then been carried on under the designation of Blackie & Son. The firm having commenced the publication of annotated editions of the Scriptures, he was led by circumstances into an extended study of biblical literature, which qualified him for a task upon which he entered with characteristic zeal, that of aiding in the editorial supervision of many of the firm's publications which demanded an acquaintance with the special knowledge he had thus acquired.

Mr. Blackie's eagerness for the diffusion of sound literature induced him to take a very active part in establishing the "Scottish Guardian," the earliest religious newspaper published in Scotland. The first number of this journal was issued in 1832, and the last in 1862. It was Liberal in politics, and evangelical in religious matters; and during the whole thirty years of its useful existence it was conducted in the spirit of its motto, an utterance of Lord Erskine - "The people of Great Britain are a free and a religious people, and, by the blessing of God, I will lend my aid to help to keep them so."

About this time the attention of philanthropists was called to the question of the better housing of the poor, and especially to the condition of lodging-houses. In this object Mr. Blackie took a deep interest. In 1847 the association for the erection of model lodging-houses for the working classes was formed mainly by his friend Mr. James Watson,(2) stockbroker, in consequence of the appalling state of overcrowding which was found to exist in the common lodging-houses of the city, with its concomitant evils, moral and physical. To substitute for such dens of immorality and centres of disease, cheap, cleanly, and healthful lodgings was the great aim of this association; and with that view three excellent houses were established by it, two for males with 423 beds, and one for females with 200 beds, all of which came to be fully patronized by the classes for whose benefit they were erected. This useful association was dissolved in 1877, but the good work it began is still continued on a more extended scale by the Corporation and other parties, the 643 beds it provided being now increased to nearly 2,000, which are uniformly well occupied from one year's end to another.

In 1857, at the request of electors of the second ward, Mr. Blackie came forward as a candidate for a seat in the Town Council, and was duly elected. He entered upon the duties of the office with his usual ardour, and, after two years, was made a Magistrate of the burgh. This office he held for four years. In 1863 he was elected Lord Provost of the city, by the unanimous vote of the Town Council, and carried into the duties of the office the zeal which had distinguished his career as a Councillor during the six previous years.

The crowded condition of many of the lodging-houses, and the beneficent efforts made to combat this evil, have been referred to already. But a far greater evil was found to exist in the city, arising from the houses in numerous localities being built too closely together, so as to exclude light and air, and induce a state of filth and disease which raised the death-rate in these localities 17 per 1000 higher than the average of the rest of the city. In order to remove these plague spots, and replace them by well-lighted, well-aired houses, and open breathing places, Mr. Blackie proposed the City Improvement Scheme (3) - a measure which, above all others, will serve to distinguish his tenure of office. This scheme was first brought by him before the Town Council on September 17, 1865, and was well received both by the Council and the citizens. When fully matured, it included the dealing with 88 acres of overbuilt ground, the formation or improvement of 51 streets, the power to expend £1,250,000 on the purchase of property, and to tax the rental of the city at not more than 6d. per £ for five years, and 3d. for ten years. The City Improvement Act was passed in the Parliamentary session of 1866, and immediately thereafter the first tax of 6d. per £, which was payable by occupiers, was imposed.

Up till this time nothing but praise had been heard of the scheme. Every one seemed pleased at the proposed removal of the dens, and the erection of well-built and well-ventilated houses in their place, but the imposition of the tax, provoked many of the taxpayers, and their displeasure fell, naturally, upon the proposer of the scheme. Mr. Blackie's term of office as Lord Provost and Town Councillor expired in November, 1866, and, being desirous to render what assistance he could in carrying through the Improvement Scheme, he offered himself for re-election. His friends were confident of his success and underestimated the annoyance of the taxpayers, or they might have prevented his defeat by the narrow majority of two votes.

While thus precluded from personally carrying out his own scheme, Mr. Blackie rejoiced to see it developed by others. There are now few citizens who do not recognize its advantages, and regard the City Improvement Scheme and the introduction of Loch Katrine water as the two most important events in the recent history of Glasgow.

During Mr. Blackie's Provostship the freedom of the city was presented to Mr. Gladstone, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, and to Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, on his unveiling the statue of his father, the late Prince Consort. He had the honour and the satisfaction of entertaining both the great Commoner and the young Prince at his residence, Lilybank, Hillhead.

In 1866 the armorial bearings of the city were authoritatively fixed for the first time by the Lord Lyon, in accordance with suggestions made by Mr. Andrew Macgeorge in an admirable history of the arms which he drew up at the time. This volume was produced at Mr. Blackie's expense, and one of his last official acts was to present copies to the Corporation and to each of the Town Councillors.

Mr. Blackie's services during the three years he had been in office were recognized by a very cordial vote of thanks being passed by the Council unanimously, accompanied with a resolution that a copy of the minute be presented to him in a silver casket. This resolution was carried into effect at the close of his civic career at a large meeting convened for the purpose, presided over by his successor in office.

Mr. Blackie was an elder of the Free Church, a warm supporter of her schemes, and often a member of the General Assembly. He took an active interest in promoting the establishment of the Free Church Theological College in Glasgow, founded in 1855 by a gift of £20,000 from Dr. Clark of Wester Moffat, on condition of other £20,000 being raised to form part of an endowment for it, and became one of the guarantors of this sum in order to fulfil the condition on which the gift was made. The ultimate success of the whole scheme owed much to his intelligent and persistent action. Being appointed a member of the Assembly's committee for negotiating a union with the United Presbyterian Church, he entered upon the duties very zealously, and exerted his influence uniformly on the side of union. He was also one of the representatives of the Free Church on the Board of the Ferguson Bequest, in the operations of which he took a lively interest; and in like manner he was identified with many other charitable and religious institutions in the city.

His health had been shaken by the overstrain caused by his labours during the Provostship. Ultimately he succumbed to a sharp attack of pleurisy on February 12th, 1873, in his 68th year. By special request his funeral was made a public one, and was attended by the Lord Provost and Council in their official capacity.

Mr. Blackie was married in 1849 to Agnes, daughter of Mr. William Gourlie, merchant, who, with their three sons, still survives.

(1) Mr. Angus was the author of a number of school books. His school was a little, dark, self-contained house of two storeys, which stood on the north side of Ingram Street, a little to the west of South Hanover Street. It was pulled down, along with the Gaelic Church which was beside it, to make room for the new block erected for the British Linen Company.

(2) Subsequently Lord Dean of Guild and Lord Provost of the City, and now Sir James.

(3) We are indebted to a gentleman intimately conversant with the working of the City Improvement Scheme for the note at the end of this article.

Twenty years have now passed since the first germs of the improvement of our City took root in the minds of the benevolent promoters of the scheme, but the causes which led up to it are fresh in the minds of many who have throughout been associated with its progress. They were mainly as follows. Old Glasgow consisted of the High Street, Saltmarket, Trongate, and Gallowgate, forming a cross, and meeting at a point called the Cross, and of streets, and wynds, and closes ranged at right angles with all these. What we now understand as sanitary laws, to be observed in the laying out of streets, and the erection of houses, seem to have been unknown or were totally disregarded by our forefathers. It is here that we find the chief cause of the necessity for our present gigantic improvement operations. In defence of our health and morals we have in due course been compelled to enter upon the improvement of our city. Were the record not too unimpeachable to be questioned, it would never be believed that the heart of a city of half a million of inhabitants contained acres of dwelling houses, of three and four storeys in height, distant from the opposite tenements in some cases by not more than seven and in others by only three feet.

Branching off from all the four principal streets above-named, there stood front to front, tenements each occupied by one hundred and fifty human beings, with neither light nor air nor conveniences sufficient for the ordinary decencies of life, to say nothing of healthy existence. So unhealthy, indeed, were these plague-spots, that ultimately none but the lowest of the population lived there, the result being that the most depraved and reckless and criminal were congregated together, and it was not even safe for any other class to visit them without protection. Passing up the old Tontine Close, shortly before it was demolished, and looking into one of the lower houses, the writer could not distinguish any of the inmates amidst the black darkness that prevailed even at mid-day. It was impossible to deal effectively with epidemic or contagious diseases in such places, and the remedy was plainly seen, when the whole facts were clearly looked at, to be nothing short of absolute and total demolition and reconstruction. Crime was as difficult to deal with in such loathsome hiding-places as physical disease, and it is with no feeling of surprise that we find our city reaching the maximum of its criminality, just before the Improvement Trustees commenced their operations.

In 1867, the year after the passing of the Improvement Act, but before any work had been carried out under it, in the taking down of properties, the number of crimes reported in the city rose to 10,899, the highest number ever reached. In 1871 - four years afterwards - they fell to 7,521, and up to this time, when seventeen years have passed, the maximum of 1867 has not been again recorded. The first intention of the promoters was no doubt guided by the above facts, but as the modus operandi was studied, the scheme necessarily enlarged itself. A healthy residential street could not be constructed out of a narrow close or wynd with its tenements nearly facing. Space sufficient was necessary in order that a wide street might be formed, with building sites on either side, and ample air spaces behind to secure the health and comfort of the inhabitants. New main sewers must also be constructed. The levels in some areas must be altered, and as the plans developed many complications arose, whose adjustment tended to widen and enlarge the scheme, and at the same time to complete and perfect it. The High Street, for instance, of which the Union Railway Company purchased a large portion of the eastern side, had so steep a gradient that traffic was most difficult and inconvenient. This was dealt with in due time, and its gradient lowered from 1 in 14½ to 1 in 29. The Gallowgate, on the other hand, was a winding course with a deep dip. Not only were its narrow closes and wynds removed, but our great eastern thoroughfare was widened, levelled up, and straightened, and brought into harmony with modern views and times.

Similar defects existed in old Main Street, Gorbals, on the south side of the river. It was therefore arranged that this ancient southern thoroughfare should be levelled up, straightened, new sewers constructed, and instead of 26 feet it was planned to be widened to 70 feet. Thus the whole character and quality of the areas were arranged to be altered and improved. It was foreseen that an effect of such works as were contemplated would be to largely increase the value of the building sites, and this was reckoned upon as the means of making the improvements practically possible, as otherwise the burden upon the ratepayers would have been too great to admit of the undertaking going forward. When the plans were at length laid down, and the values of the new sites estimated, stances which prior to the improvements were 20s., 30s., and 40s. per square yard at market value, were expected to be worth, after the alterations, three and four times these sums. And when the time for re-construction actually arrived, with the roads and sewers made and the pavements laid, builders and others vied with each other in securing the sites, and they frequently brought even more in the open market than had been arranged for. It must be borne in mind that no properties or sites are sold by the Trust otherwise than by public auction after due notice by advertisement.

It was early seen that no improvement of the kind indicated could be completed without affecting the value and price of the contiguous properties. It therefore became necessary to complete all purchases in any given area before beginning to work upon it, otherwise the prices of all unbought properties would have been raised by the operations of the purchasers themselves. In order, also, that the sites in any given area should be seen at their full advantage, and intending feuars be able to estimate their suitability and proper value, it was necessary that the whole area should be laid out, the streets widened, the roadways levelled, the causeways laid, and the new character of the district made clearly visible and apparent. While this was being done, and until revenue came in from the building sites disposed of, the whole burden of the charges and interest had to fall upon the ratepayers. It was therefore wisely resolved not to operate upon more than one area at once, and only to commence upon a new one when the sites of the one preceding had been mostly sold. Such was the eagerness, however, to secure Improvement Trust feus, that an area could scarcely be completed before many of the sites were taken up, and this eagerness caused some annoyance to the management, as complaints of not finishing areas were made before time would permit the consolidation of the ground acted upon, and the full completion of the work. Bridgeton Cross, Ingram Street, Gallowgate, Calton, Gorbals, and High Street had in turn been dealt with, and remaining sites were selling freely, when it became a question with the Committee, since the Union Railway Co. had taken down many of the properties in the Bridgegate and other streets in the line of their works, whether the Saltmarket should not be acted upon. It seemed very advisable to co-operate with the Railway Co. in dealing with this area, and it was at length resolved to take down the east side of Saltmarket, and this was done. The Calton ground was not yet feued, but at this time employment in all industries was abundant, not in Glasgow only, nor in Scotland only, but throughout Great Britain, continental Europe, and America. All values had increased. Workmen's wages had gone up from 20 to 50 per cent., and even higher in some branches. Merchandise of every description had risen vastly in value, and no gloomy cloud was seen upon the horizon of commerce. Old properties, the material and wages of which bore no proportion to the costs of the new, sold at prices unknown in former times, and not only in Glasgow but in every considerable town opportunity was seized for speculation, which was engaged in to an inordinate extent. Rents were demanded beyond what could be legitimately paid, and in Glasgow, when the inevitable reaction came, and reverse and loss were wide-spread, the City Improvement Trustees felt the shock with no ordinary violence.

In the autumn of 1878 the first sign of the coming storm appeared. The City of Glasgow Bank stopped payment. Properties of all kinds immediately felt the scare. Building operations ceased. Many partly-erected buildings were deserted as they stood, and remained as vestiges of the sudden desolation. It was soon found that some of the Improvement Trusts feuars were in difficulties, and all thought of further operations was suddenly and for the time entirely suspended. Many workpeople, especially in the building trades, left the city, though everywhere the same reaction had arisen, and there was everywhere a dearth of employment. It was soon seen that building had been going forward at a rate greatly beyond all precedent, and that many years must elapse before the steadily increasing population could overtake the supply. The number of dwelling houses, occupied and unoccupied, within the parliamentary boundary in 1866 was 93,386, and of these only 1,763 were unoccupied. In 1879-80 the number of dwelling houses, occupied and unoccupied, was 113,881, and of these 11,433 were unoccupied. This reads its own lesson as to over-building.

A part of the scheme which had been reckoned upon as likely not only to beautify the city, but also to be very remunerative to the Trust, was the reconstruction of the Saltmarket and the improvement of the Trongate. This was now indefinitely suspended. The latter street was planned to be widened from King Street to the Saltmarket, at which point it was to be 110 feet wide from the old Tontine corner. Fabulous prices were at one time named as likely to be paid for sites when this old historic business centre came to be reconstructed. Calmer and wiser counsels now prevail, but there is little doubt that when the scheme is ultimately carried out, the old Cross of Glasgow will re-assert its claims to popularity, and as a central market for eastern and country traffic it will again take a first place within the city.

The entire cost of the Glasgow Improvement Scheme to the ratepayers cannot, in view of the large areas still to be worked upon, be properly determined. Sites are now lying vacant, upon the purchase price of which interest must continue to be paid until they are sold. No reduction of price would stimulate a healthy demand; when that sets in, fair prices will readily be offered, and we have the assurance of the Trustees, frequently repeated, that they will not be hard to deal with. But while we cannot determine with any certainty the final financial results of the Trust, we can form a pretty accurate estimate of how we presently stand in regard to it.

In 1866-67 the Trustees laid their first assessment at 6d. per £. From our present standpoint it does appear that they exercised their powers with too unsparing a hand. The levy created such an outcry that Lord Provost Blackie, one of the chief promoters of the scheme, lost his seat in the Council. The next year the rate was reduced to 4d. per £, and so remained till 1870-71, when the largest amount in any one year was realized from the assessment, viz., £30,867 7s. 5d. During 1871-72 and 1872-73 the rate was lowered to 3d. per £. In 1873-74 it was further reduced to 2d. per £, at which sum it has remained till 1883-84, after which it is arranged to be 1½ d. per £.

The total sum contributed by the city in rates up to 31st May, 1884, amounts to £443,571 3s. 4d., and the last balance sheet (in consequence of the largely reduced valuation of the Trust's properties) shows a deficiency of assets, which of course the citizens must make up, of £59,147 1s. 4d. These sums taken together, viz., £502,718 4s. 8d., give a pretty closely approximate idea of what the scheme will cost the citizens. It is only fair to bear in mind, however, that the citizens have secured for their own convenience 92,722 square yards of ground, which they have appropriated to the formation of new streets and the widening of old ones. They have also laid out in paving and sewer works, etc., £101,877 9s. 9d., and they have purchased for themselves at a cost of £40,000 the Alexandra Park, all of which sums are included in the above amount, and represent together a value of something like £373,682. For the outlay one of the greatest and most thorough improvements ever undertaken by a city has been accomplished. A goodly heritage remains to the citizens of all future ages, and it may be said of the far-seeing founders of the Improvement Scheme, and of us who have paid for its development, "si monumentum quaeris circumspice."

The purchases of the properties were made with the utmost caution. The old rentals were chiefly taken as the basis of value, and the number of years' purchase was fixed upon after the most careful consideration of all matters bearing upon each separate case. In a scheme so vast, with such multifarious details, it could not but happen that lapses should occur. These were singularly few; the compulsory powers, with appeal to a jury, while necessitating the offering of a full and liberal price, generally sufficed to keep sellers within reasonable bounds. No exceptionally high price was in any case given which could rule as a precedent, or affect the general policy of the Trustees in buying. Of course in taking properties from sellers under compulsion, considerably higher rates were given than would have been arranged for if the purchases had been made under voluntary offer.

The Trust has also been of immense benefit to the city through its extensive lodging-house investments. There are seven model lodging-houses in all, six for males and one for females. Their aggregate cost, including ground, has been £87,170 13s. 7d. The average number of lodgers during the past year was 1,912, the total number of beds being 1,963. The citizens are put to no expense on account of these houses, for the total charge for the past year, including interest, was £10,612 while the gross annual revenue paid by the lodgers was £11,020. Thus, in cleanly, comfortable lodgings, at a minimum of cost to themselves, provision is made for our poorer neighbours, who have ample and well-ordered cooking requisites, large airy sleeping and day apartments, comfortable washing arrangements, and that complete supervision which is so indispensable in dealing with this too commonly heedless and unthrifty class.

The large open space opposite the Cathedral, the covering in of the Molendinar and Camlachie burns, the formation of the wide and graceful avenue up through the Bridge of Sighs intended to be carried forward to the Alexandra Park, these and many other works might be mentioned, but minute details are not consistent with the object of these notes. Nor is any reference necessary to the vexed questions that have from time to time claimed the attention and tried the temper of the Trustees. It is sufficient to know that a great and salutary and patriotic work was intended, and has been as far as possible successfully accomplished. That disappointment has for a time intervened, and general discomfiture overtaken all classes of property owners, and bad times led to a general outcry in all commercial circles, is no good reason for raising any suspicion against a work in itself essentially good, and formed to endure through all the vicissitudes of coming cycles of prosperity and depression. As trade and commerce revive and our population increases, whether from natural growth or from immigration, all spare building sites will be readily taken up, and in due course, without any attempt at forcing events, the operations of the Trust will be completed.

Back to Contents