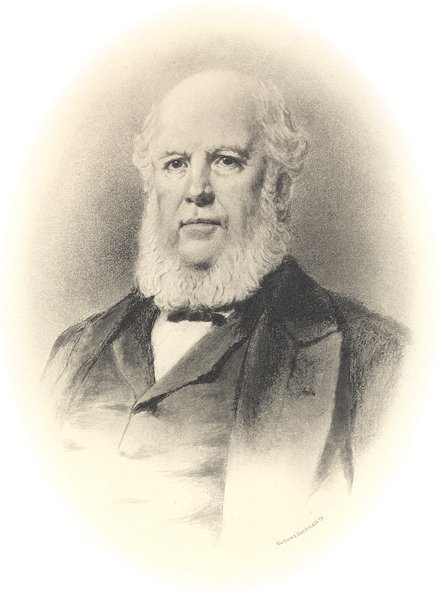

Son of proprietor of a Lennoxtown printing firm, Dalglish was born in Glasgow on 4 January 1808 and educated at the University of Glasgow before starting work in the family business.

His father - also Robert Dalglish - was Lord Provost of Glasgow in 1832 at the time of the Reform Bill, and Dalglish himself took an active interest in politics from 1857, when he stood successfully for parliament as an independent Radical. He retained his seat in three further elections (1859, 1865 and 1868), before retiring in 1874.

He was an admirer of the Duke of Wellington and was prominent in the erection of Marochetti's statue of him in front of the Glasgow Royal Exchange. Dalglish's portrait appears on one of the bas-reliefs on Queen Victoria's statue in George Square. He died on 6 June 1880.

IN the year 1803 Robert Dalglish, his brother Alexander, and Patrick Falconer leased thirty-three Scots acres from John Lennox of Woodhead and commenced business as calico printers under the firm of R. Dalglish, Falconer, & Co. at Lennoxtown, where the same firm still carries on the same business. From the first the company had many foreign customers, and a significant entry of the expenses of an establishment at Heligoland tells how the goods reached them. It was the time of Napoleon's Berlin and Milan Decrees, by which he sought to close the Continent to our manufactures, and Heligoland was one of the most important stations for running the blockade. Robert Dalglish, the founder of the firm, was born in the year 1770, and bred in the warehouse of Andrew Stephenson, muslin manufacturer, Bell Street. He was a man of mark and standing in his day - one of those quiet workers that have helped to make Glasgow what it is; a shrewd, cautious, sensible man, looked up to and esteemed by every one. The trust and regard of the people of Glasgow stood him in good stead in troublous times, for he was Lord Provost at the time of the Reform Bill in 1832. He was far from being a reformer, yet to keep control over the movement he put himself at the head of it, presided at the meetings of reformers, and headed one of the great processions. He was equally active in good works. In a flood which occurred during his provostship, he not only sent relief to the inundated districts, but took it to them with his own hands, sailing about the Briggate in a boat. By his wife he had two sons, Andrew Stephenson Dalglish, born 1793, died 1858, a man of great force of character, and much liked by those who knew him;(1) and Robert, who was born at Glasgow on the 4th of January, 1808, and died on the 6th of June, 1880. After finishing his education at the University of Glasgow Robert was sent to his father's works at Lennoxtown, where he lived for long in a house near the works known as "The Cottage."

Till the year 1857 Mr. Dalglish devoted his whole attention to his business, which he increased greatly, and brought his Works to a high state of efficiency.

In 1857 John McGregor, one of the Members for Glasgow, resigned, and the late Walter Buchanan was chosen in his stead; but the election was scarcely over when a dissolution took place. At the new election in March, 1857, Mr. Dalglish stood as an independent Radical, in favour of extension of the franchise, vote by ballot, a more equal distribution of electoral districts, and an extended measure of education, etc. From these principles he never swerved, though latterly his views on most political subjects were not so advanced as they had been at one time. Much abuse was lavished on him at the time for his courageous advocacy of the opening of the Botanic Gardens on Sunday afternoons, and, generally, a bitter fight was waged, but on the 31st of March the result of the poll was - Buchanan, 7,069; Dalglish, 6,764; Hastie, 5,044.

Mr. Dalglish was returned again in 1859, in 1865, and in 1868, and retired in 1874. Never was there a more popular member than Robert Dalglish. From the first his terse, racy speeches attracted the electors of Glasgow, and his dealing with "hecklers," was simply masterly. To all questions that bore on important matters he gave short, clear answers, but to crochet-mongers he was merciless, to the delight of his audience. For instance, to an elector, it is believed the redoubtable James Martin, who asked if he would support a bill for the payment of Members of Parliament, Mr. Dalglish answered that he would not, as he saw so many gentlemen paying large sums to get in. When in the House, it is not too much to say that he has been equalled by few and surpassed by none as a good and efflicient member for Glasgow. And, mirabile dictu! he was much liked by, and had great influence with the Irish members, so much so that it was said he could always get a couple of dozen of them to vote for or against any bill affecting the interest of his constituents.(2) He luckily was not a speaking Member, nor did he make confusion worse confounded by dabbling in amateur law-making, but his ability and sense gradually gave him an influence very much greater than was possessed by Members who bulked more in the public eye. His time, his labour, and his influence were given not only ungrudgingly, but cheerfully, to any constituent that had need of them; and he looked after the interests of Glasgow both watchfully and energetically. A journal that is not given to speaking too well of dignities, "Vanity Fair," gave in 1873 the following notice of Mr. Dalglish, and, after allowing for caricature, it is a fairly truthful sketch - "Popularity is commonly but a poor test of merit, yet in Parliament it has a distinct value and meaning, so that Mr. Dalglish may well be proud of being known for the most popular Member of the House of Commons. He has in truth all the qualities which command consideration among a body of ordinary sensible men. He possesses the charity that is not puffed up, he is an easy-going, good-natured man, he is fond of the fair sex, he gives good dinners, and yet at the same time he has a sound judgment and discretion, often appealed to by men whose names are far more frequently before the public. He is one of those valuable and too rare Members who are useful in Committee, and seldom speak at all, and never without saying something to the point at issue and worthy of being ranged among the arguments concerning it."

Any account of Robert Dalglish would be incomplete did it not notice his wondrous hospitality. In London he gave many dinners, but the best of his entertaining was done at Kilmardinny, which he had bought in 1853. To show that he allowed no political prejudices to interfere with his hospitality, it may be mentioned that both Mr. Disraeli and Mr. Bright were his guests there on different occasions. Kilmardinny, indeed, is remembered regretfully by his friends, and they were legion, as the one house above all others where real hospitality was practised. Fabulous stories were told of the size of the claret glasses, and the flavour of the pines; but no fable could exaggerate the humour, the geniality, and the kindness of the host.

(1) He was a great admirer of the "Iron Duke," and took a prominent part in getting up the statue to him by Marochetti, which stands in front of the Royal Exchange. Partly for his exertions in that matter, and partly as a mark of the esteem in which lie was hold by his fellow-citizens, they gave him a public dinner in the Trades' Hall in October, 1844, which was attended by most of the principal citizens, as well as by others in the West of Scotland, and proved a great success. His portrait is on one of the bas-reliefs on the Queen's statue in George Square.

(2) On one occasion a friend of Mr. Dalglish's was talking to him in the Lobby of the House when a Member approached and said, "I say, Dalglish, what was that Bill you wanted me to vote on?" Mr. Dalglish told him. The Member was going off when he turned and said, "By the way, how am I to vote ?"

Back to Contents