Born near Hamilton, the son of a weaver, Logan was greatly affected by seeing a Glasgow missionary die of typhoid. He went to work with sufferers of the disease in London and Leeds. From 1840 to 1842 he was in Rochdale, returning to Glasgow where he attended classes at the university while working as a missionary. He also spent time in various prisons, studying the causes of crime, before undertaking a second spell of missionary work in northern England.

His interest in the arts led to his erecting a monument to the memory of David Gray, the Kirkintilloch poet, and he was a close friend of Janet Hamilton, the Coatbridge poet.

He died on 16 September 1879.

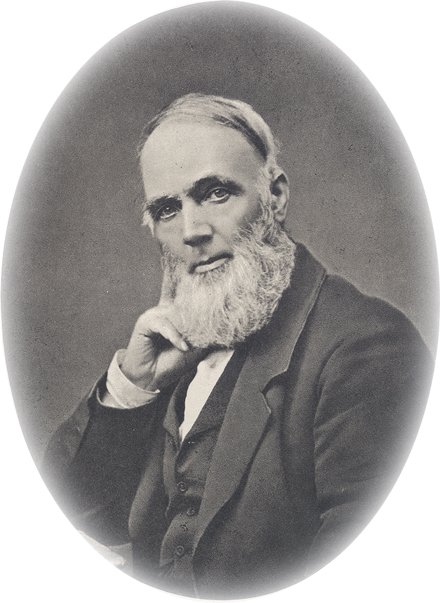

WILLIAM LOGAN was born at Damhead, near Hamilton, in 1813, of the hardy, god-fearing, westland race among whom the traditions of the Covenant have lingered longest. His father was of Silas Marner's calling - a "customer weaver," and was distinguished by the thoughtfulness and intelligence which that calling tends to foster. William tried several employments in Hamilton and Glasgow, but, with the restlessness of one who has not yet found his true vocation, he felt them to be uncongenial. In Glasgow he came under the influence of Dr. William Anderson, whose intensity laid firm and lasting hold of the young enthusiast. Along with his pastor he watched by the death-bed of a city missionary named Nisbet, smitten with malignant typhus, and was greatly moved by some words spoken in a lucid interval by the dying man. These two influences, of the living and the dead, helped to shape William Logan's future. He returned to his father's loom, but dreamed as he wrought of mission work abroad, and spent all his leisure in mission work at home. About this time David Nasmith, the founder of city missions, lectured in Hamilton. The lecture, and subsequent conversation with the lecturer, led William Logan into the field in which he won his laurels. He was sent to London for three months' probationary service in the notorious district of St. Giles. One of the streets allotted to him was the "Gibbet Street" of Dickens, in which the offscourings of all things had their haunts. Here the young recruit learned to endure hardness; sometimes, that he might reach a door, creeping on hands and knees across a plank which bridged a chasm; sometimes followed down-stairs by a shower of burning cinders; and sometimes interrupted in his meetings by fighting dogs introduced on purpose to disturb him. But he did his work with courage and with tact. He would enter a den of thieves, and resisting an impulse to read the parable of the Prodigal Son, because he thought "it would be too personal," he would expound the Ten Commandments, not without manifest impression on his audience of law-breakers.

Having approved himself to Nasmith he was sent to assist in organizing a mission in Leeds, where, in addition to his district work, he spent some hours daily in the Infirmary and Fever Hospital, not shrinking from contact with a deadly type of typhus then epidemic. From Leeds he was sent in 1840 to Rochdale, where he remained two years, coming into close relation with John Bright, who, in earnest labours to promote education and temperance and to relieve a prevalent distress, was even then beginning to reveal his power. From Rochdale he came to Glasgow with the purpose of qualifying himself for the foreign field. He attended classes in the University and in the Andersonian, working meanwhile as a missionary in the High Street. Not content with prescribed duty, he set himself to study the social phenomena around him, giving special heed to the necessity for sanitary reform, for education, and for temperance, and gathering the results of his experience into a volume on the "Moral Statistics of Glasgow," which was long a hand-book for those interested in ameliorating the condition of the poor in great cities. The early impressions made at Nisbet's death-bed led him, here as elsewhere, to give special attention to those suffering from fever. For three months he was so entirely occupied in infected houses that he deemed it better not to visit any healthy family. He was accustomed to say that when he escaped from the tainted air in which he spent his days to the open spaces of the town he felt as if he had passed into the suburbs of Paradise.

At the urgent request of Mr. Bright he was induced to return as a missionary to Rochdale, having, before entering on this engagement, enlarged his experience by spending, with consent of the Secretary of State, a considerable time at Millbank and Pentonville in examining the causes and accompaniments of crime. After another period of service in Scotland, he was again led to undertake mission work in Yorkshire, Bradford being the central town in which he not only did the work of an evangelist, but organized courses of lectures intended to meet the doubts and perplexities of working-men.

The intense and unresting labours of years spent in contact with the most degraded classes, with malignant types of disease and loathsome forms of vice, told upon the constitution of the eager worker. At the early age of forty he found himself with ardour unabated and with his boyish dream of foreign service as bright as ever, but face to face with the urgent need of rest. His earnest sympathy with the cause of temperance led him to establish a small temperance dining-room, which grew under his careful eye till it became a source of modest wealth, which he spent with lavish hand in ministries of loving-kindness.

His sympathies were not, as in the case of some philanthropists, circumscribed. They were far-reaching and intensely human. He had a native refinement which his contact with social degradation had only served to make more refined. He had the keenest appreciation of the beautiful in literature and art, and nothing delighted him more than when he had the opportunity of lending a helping hand to any struggling wielder of the pen or the pencil, on his way to fame. He is specially identified with the brief and tragic history of David Gray, the poet of the Luggie. He had discovered his worth and genius before the young poet left for London, and through his interest in him was brought into friendly relations with Lord Houghton, who found in William Logan a trusted agent through whom he could continue to young Gray, after his return to Scotland, the kindness he had shown him in the South. Logan's ministries of love to the poet were unwearied. He regularly visited him, and helped to soothe his dying hours. When the end had come he set himself to the double task of raising a monument to his memory in the "Auld Aisle" Burying Ground, Kirkintilloch, where he lies buried; and of collecting a fund for promoting the comfort of his mother. He entrusted the fund to other hands, but charged himself with the duty of personally conveying to Mrs. Gray the sums paid to her at regular intervals.

He was also the constant friend of Janet Hamilton, the poet of Coatbridge. He not only showed her all manner of friendly attentions, but did more perhaps than any one else to bring her into fame, buying her books largely and sending copies to influential critics who might otherwise have failed to notice them. If any young minister was in trouble through charges of heresy, William Logan was sure to find his way to his side and cheer him with his sympathy. His "Words of Comfort for Parents Bereaved of Little Children" - the idea of which was suggested by the help he obtained from friendly letters when his girl Sophia was taken from him at the age of five years - have gone far and wide into houses of mourning and have been stained by blessed tears they have helped to bring. There were thousands he had never seen who felt that they had lost a friend when it was announced that on the 16th September, 1879, William Logan had passed away.

Back to Contents