The author of 100 Glasgow Men, MacLehose died on 20 December 1885, just before the book went to press. His friends added his biography to the existing number.

The son of a weaver, he was born in Govan on 16 March 1811 and from 1823-1830 served an apprenticeship with the bookseller George Gallie before working in London from 1833-38. On his return to Glasgow he established a business in Buchanan Street along with Robert Nelson, taking sole charge in 1841 and moving premises to St Vincent Street in 1849. The company became one of the largest UK book retail businesses outwith London.

Prior to 100 Glasgow Men, MacLehose had published another of his own works, The Old Country Houses of the Old Glasgow Gentry (1870, then revised and enlarged in 1878). He was bookseller to Glasgow University, to the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, and to the Faculty of Procurators.

SUDDENLY called away just when he had the prospect of a quiet evening after a laborious day, just as he had given the finishing touches to his magnum opus!

The idea of this book was his, and only he could have carried it out; he had spared neither money nor pains to make his "Hundred Glasgow Men" a fine specimen of Glasgow work: the paper was specially made, the printing, the binding, the lettering on the back, the medallion on the board, the very ink, had his special care: every line had passed through his own hands, and his characteristic preface was almost the last thing he wrote.

Fortunately the second volume was not yet bound, and his sons were urged from many quarters to allow their father to be added to the "Hundred." With their consent the roll ends appropriately with a short notice of him.

In any case the book would have been incomplete without him. For James MacLehose was made of the same stuff as the biggest of the "Hundred." He had the same business insight and courage and mastery of details, and he, a Govan boy with no funds or friends, no resources outside of himself, built up a business in its own line as notable as Gartsherrie or Fairfield.(1)

But he had other and higher merit. We have plenty of eminent business men who, outside their business, are as commonplace as the rest of us. MacLehose had a character as marked as his features.(2)

The first of him was the worst of him. He had a blunt manner and a quick temper. But the rough husk was not ill to pierce, and only added gusto to the kernel. A dour Scotchman, "as het as ginger and as steeve as steel," who prided himself on having mastered his business and fought his own battle, he would not defer to his best customer. But his best customer and the customer who was not worth £1 a year to him, alike had his scrupulous attention and straightforward advice - it was not his fault if they did not get the worth of their money.

For money he had a proper value.

'Twas no' to hide it in a hedge,

No' for a train attendant,

But for the glorious privilege

O' bein' independent."

But to help a good case he was liberal of his money, and lavish of his time, which to him was money. Gentlewomen reduced by disaster to earn their bread by teaching, or painting, governesses, students, literary beginners, in the weary quest for work, came to him quite naturally, and did not come in vain. His great knowledge of books, and the grand stock he had the courage to keep, brought a stream of people about him. But the customer constantly returned as the acquaintance or the friend, or to seek advice on worse difficulties than the choice of a book. MacLehose had many a confidence, but he never betrayed the trust: he was on an intimate footing with many of the best people in Glasgow and in the West of Scotland, and had all the news of Town and Country; but discreditable facts, if he did name them when they had become public property, he named as if they pained him.

For many of us his death is not only the loss of a friend: like Norman Macleod's death, it is the 'scaling of the byke,' the loss of the recognized centre for a large circle. His back shop was the first call after an absence. One seldom missed finding friends there, and never missed a hearty grip from the big hand.

MacLehose was proud of the writers he got to write this book for him, over fifty of them - 'no literary hacks,' he said - all volunteers, some of them professors, some ministers, most of them 'Glasgow Men,' well known bankers, merchants, lawyers, busy men not used to write for the press, but one and all working with a will under a master whose geniality and humour, tact and patience, won their hearts day by day. The 'prentice hand may be traced in their papers, but only they could have given him the private information which gives this book its special value, and only he could have got the team together or driven them straight.

We were all counting the days till the magnum opus should be out, and we could drop in and shake hands with our old friend over the success of his enterprise. But the big head is low, and the hand has lost its grip, and our main interest in the book is gone.

James MacLehose's life was one of few events. He was the son of Thomas MacLehose, weaver, and was born in Govan on 16th March, 1811; in 1823 was apprenticed here for seven years to George Gallie, bookseller (3); in 1833 made his way to London to Seeley's well-known house; in 1838 returned to Glasgow, and began business at 83 Buchanan Street with Robert Nelson as J. MacLehose & R. Nelson; in 1841 took over the business, and continued it in his own name; in 1849 moved to 61 St. Vincent Street, which, with additions, he occupied to the end; finally in 1881 assumed his sons, Robert and James, under the firm of James MacLehose & Sons.

In 1850 he married the eldest daughter of Mr. John S. Jackson, banker, Manchester, who survives him with three sons and four daughters.

His life was very methodical. He was to be found all day and every day at his post, generally at the familiar desk in the back shop; always busy, yet always ready to be interrupted. Taking the care he took over every detail, and keeping himself abreast as he did of the literature of the day, how he was so patient of interruptions and how he got through his work we never could understand; nor how he managed to write so many notes in that curious hand of his. His usual hour of leaving was six o'clock. On the 11th of December, after putting some finishing touches to this book, he went home early, feeling tired. On the 15th he was struck down by paralysis, and never rallied. He died on the 20th of December, 1885. He was seventy-four. No one seeing his youthful spirit would have thought him so old.

We would close this notice by recalling two early friendships of MacLehose's, of far older date than the circle he latterly gathered round him.

David Livingstone was a friend as far back as the old Blantyre days, and was a frequent correspondent in after years. On the morning when he left this on his first missionary venture, he started on foot from Blantyre at three o'clock, and the two friends breakfasted together before daylight in MacLehose's back shop in Buchanan Street, and parted at the Broomielaw.

A more important friendship, the most important factor in MacLehose's life outside of his own home, was his lifelong friendship with Daniel Macmillan. There are many notices of MacLehose in Macmillan's delightful Life by Thomas Hughes. The two had met here as lads, and were friends ever after - proof enough of MacLehose's worth. MacLehose was the first to go to London, and when Macmillan followed him, MacLehose shared with him his bed and his board; he plied him with introductions and information; and when Macmillan, with the weak nerves of a chronic invalid, was ready to despair, MacLehose's sympathy and hearty spirit bore him up. The two friends had little leisure to see each other on working days, but for years every Day of Rest found them sitting side by side in the Weigh House Chapel; and long after, when MacLehose had been years back in Glasgow, Macmillan, in acknowledging some service done to a nephew, writes to him - "It brought me back good old MacLehose with his kindness, his heartiness, disinterestedness, the same good old reality, who was becoming a kind of shadow to me or little more. There he is again, not talking but doing something for you."

The Macmillan influence did something to shape MacLehose's character and career, and to stimulate his efforts to make Glasgow a seat of literature as well as of commerce. Here is one of Macmillan's letters when still a shopman at £80 a year - "Bless your heart, MacLehose, you never surely thought you were merely working for bread. No, no, Mac.! That won't do. We booksellers, if we are faithful to our task, are trying to destroy, and are helping to destroy, all of confusion, and are aiding our great Taskmaster to reduce the world into order, and beauty, and harmony. Bread we must have, and gain it by the sweat of our brow, or of our brain, and that is noble, because God appointed. Yet that is not all. As truly as God is, we are His ministers, and help to minister to the well-being of the spirits of men." The two friends were alike in their high ideal of their craft. They were alike too in their early struggles for the independence that was a passion with both. Macmillan's Life tells us how long and hard a fight he had; and MacLehose as slowly and painfully 'speiled the brae.' He might have climbed quicker, but from the first he would have nothing but of the best, and a sore struggle he had for many a day to keep his feet. We may be sure neither of the friends in after life regretted the discipline that "gies the wit of age to youth."

(1) He had one of the largest retail book businesses out of London. His circulating library, begun in 1841 on four shelves of a bookcase, grew to over 20,000 volumes, and is now one of the first half-dozen in the kingdom. His binding branch, begun, in 1863, because he could not get his work done for him to his mind, was constantly growing in size and reputation; he spread a taste here for fine binding, and latterly had work regularly sent him from London, past the doors of Bedford and Riviere. In his printing, done for him by his brother, Robert MacLehose, he aimed at nothing short of the Foulis standard. As a publisher he issued, more especially during the last fifteen years, books perhaps of a higher class than had before been published in Glasgow. Two of his books had a special interest for him, not for their intrinsic value only, but also as being specially his work - the "Old Country Houses of the Old Glasgow Gentry," and this book, which he designed as a sequel to it. He was publisher and bookseller to the University, and bookseller to the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, and to the Faculty of Procurators.

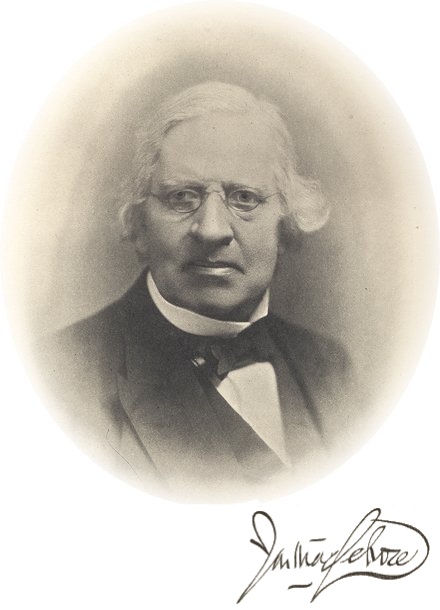

(2) A most characteristic likeness of him is reproduced for this memoir from a photograph taken in London last spring, when for a wonder he treated himself to a short holiday. To the reproduction of this is subscribed his autograph in facsimile. Many will be glad of this reminder of the curious hand he wrote: and wonderfully quick he wrote it, and many a humorous note he rolled off in it. The writer may be allowed to acknowledge here a characteristic piece of kindness in connection with the London visit just mentioned. On behalf of a friend he had asked Mr. MacLehose if he could in London get some information connected with his particular trade. The information was got, and was of the greatest service; but it afterwards turned out that in order to get it Mr. MacLehose, out of his short holiday, had spent an entire day driving about London.

(3) George Gallie's shop was first in Brunswick Place, then in Glassford Street, and finally in Buchanan Street, where, in new hands, the old name remains. Thomas MacLehose could not have sent his boy to a better school for honesty, industry, and thoroughness, nor to a worse school for manners. Gallie was a 'kenspeckle' character - at bottom a man of rare virtue, true and tried, at top undoubtedly trying. A man of few words, he gave you an answer at the time and in the way that pleased him. To a good many people he was known as "Clim'," in this wise. A lady who had many dealings with him asked him one day for a certain book. He was at his usual desk, and answered by pointing with his pen to a shelf. The lady, seeing the book high above her reach, ventured, after waiting some time, to express her difficulty. Gallie jumped up from his desk, flopped a ladder against the shelving, and, with the word "clim'," resumed his writing. A man of clear-cut opinions and high principle, he would not budge an inch for any man or number of men. He was a voluntary, and on the day of a public fast for the cholera, when weak-kneed or puzzle-headed brethren followed the multitude to church, Gallie, it was said, opened his shop at six in the morning. He dealt mostly in tracts and religious books. Nothing would have tempted him to keep literature that he disapproved of. It was a favourite joke of young scamps to ask him for "Punch." "Punch"! he would have kicked it on to the pavement, as he was said to have actually done to an obnoxious packet. After all, matter outweighs manner, and it would be well if we had more George Gallies. Men of stiff-backed sterling principle are wanted in this limp pinchbeck age.

Back to Contents