Born in Fintry, Stirlingshire, on 4 June 1806, Macnee was raised by his mother and soon moved to Glasgow. He showed great ability in drawing and at the age of 12 was apprenticed to the popular Glasgow artist John Knox.

After four years he was employed by Hugh Wilson, an engraver, and also produced anatomical drawings and painted snuff-boxes. Moving to Edinburgh, he began to have his pictures accepted in exhibitions, gradually establishing himself as a portrait painter.

He became president of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1875 and also received a knighthood. In the last two years of his life he received honorary degrees from the universities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. He died in Edinburgh on 17 January 1882.

This distinguished artist was born in the little village of Fintry, in Stirlingshire, on the 4th of June, 1806. His father, Mr. Robert Macnee, died when Daniel was an infant, and he was brought up by his mother, a very superior woman of the fine old Scotch type. Her son always spoke of her with admiration, and to her careful and judicious training he ascribed his success in life. While he was yet a child his mother removed to Glasgow, chiefly with a view to his education, of which she was very careful; and from his earliest years she was particular about his choice of companions.

From his boyhood he showed a strong predilection for drawing, and in this he found, in Glasgow, a congenial spirit, a boy about the same age, William L. Leitch, who achieved such high eminence as a water-colour painter. They were much attached to each other, but they were not school-fellows. Macnee went to the school of Mr. Marshall, a somewhat superior academy, while Leitch was sent to the school of Mr. John Miller, in the locality then known as the Limmerfield. Macnee and his mother lived at that time in the Kirkgate, and Leitch, who lived with his parents nearly opposite the Cathedral, spent much of his time in his friend's house, usually three or four nights in the week, when the boys used to practise drawing together.

As Macnee grew up his love for art increased, and he expressed a strong desire to follow it as a profession. His mother was at first opposed to this - influenced by a prejudice not then uncommon, that it was not a respectable occupation; but she yielded when she found that the boy was bent upon it, and then she resolved that he should have a proper artistic education. With this view, when he was little more than twelve years old, he was apprenticed to an artist then very popular in Glasgow, Mr. John Knox, who, besides practising his art as a landscape painter, in which he was very successful, taught drawing. His house was in Dunlop Street. Leitch, who, much against his will, had been sent to learn weaving, used to tell how he envied his friend's good fortune, and how he often went to tell his sorrows to Mrs. Macnee, whom he described as "a very kind, motherly person." Macnee sympathized with Leitch, and used to lend him, to copy, little paintings which he had done with Mr. Knox.

Macnee was fond of theatricals, and went occasionally to see the performances in a small theatre, known as Mason's Circus, immediately opposite Mr. Knox's house in Dunlop Street. He was attracted as much by the scenery as the performances, and he took great delight in studying it. Some of the scenes, indeed, were worthy of his notice, as they had been painted by David Roberts.

At a later period Macnee and Leitch joined some other lads in getting up a club for theatrical performances. For this purpose they hired a room in Saltmarket Street, but they soon removed to a larger place - a cellar under the Lyceum Rooms in Nelson Street - where they had frequent performances, and where Macnee and Leitch painted the scenes. Leitch, writing to a friend of this time, says - "Macnee, who at that time was a slight, elegant young fellow, did Frank Osbaldistone very well, and sang the songs capitally." Some of the lads took the female characters. This was in 1820. Subsequently the club hired a place in Buchanan Street, but both Macnee and Leitch soon afterwards left it. Of their employment while they were members, Leitch wrote - "Macnee and I were always busy with our special work - the scenery - and that gave us practice. To Macnee it was amusement. He was so light-hearted, so lively, so merry, so possessed by the most agreeable and buoyant faculty of imitation and invention, that all he did in the way of painting seemed mere pastime; whilst with me it was serious work, una cosa seria. My friend seemed to be able to do all that I could do, and fifty times more, without giving the matter a thought."

Macnee was about four years with Mr. Knox, but during all that time he was, at his leisure hours, acquiring much general knowledge by a course of useful reading. On leaving Mr. Knox, he was employed for about a year by Mr. Hugh Wilson, engraver, in making lithographic drawings on the stone; and he also at this time executed some anatomical drawings for Dr. James Brown to illustrate a course of popular lectures on anatomy which he was then delivering in Glasgow. After this he went to Cumnock, where he was employed in the painting of snuff-boxes, then a branch of industry in which many young artists, including Leitch and Horatio McCulloch, found employment in their earlier artistic career. But he remained little more than a month there. Mr. Lizars, a well-known engraver in Edinburgh, who had heard of the anatomical drawings made for Dr. Brown, invited Macnee to enter his employment, which he did; and when in Edinburgh he became a student in the Academy established by the Board of Trustees for the Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures, then under the superintendence of Sir William Allan, where he distinguished himself chiefly by the accuracy of his drawings from the antique.

When in Edinburgh, McCulloch and he were constant companions, and they shared the same rooms. Another of his companions there was Mr. Forrest, well known afterwards as an engraver, who also worked with Mr. Lizars. Speaking of this time, Mr. Forrest used to say that a wilder or more boisterous set of young men than the apprentices at Mr. Lizars' it would be difficult to find. In all the fun and sport that went on Macnee was ever the leader, but in the midst of all his mother's training showed itself. He would never be a party to anything improper, and so great was his influence over his companions that none of them dared to utter an oath or a coarse word when he was present. All this time he employed his leisure in practising drawing and painting, and he took great delight in visits to the annual exhibitions of pictures. One day he was in the Exhibition, when Sir William Allan, the President of the Academy, introduced him to Sir Walter Scott as a promising young artist, and Sir Walter conversed with him for a short time. Macnee used to speak of this as one of his most pleasing reminiscences.

His pictures were now finding a place in the Exhibitions both in Edinburgh and at Glasgow. He did not at first confine himself to any particular line, but painted landscapes and genre pieces as well as portraits - some of them so fine as to show that to whatever line of subjects he had chosen to devote himself he would have achieved eminence in it; but he gradually came to confine himself to one, and became by profession a portrait painter.

In 1832 he went to England, and there painted a number of portraits. He painted a considerable number in the county of Kent, where he resided for some time, - among others, portraits of General le Mesurier, and Sir Henry, afterwards Lord Hardinge. The last-mentioned was the first portrait he exhibited in the Royal Academy. On his return from England he settled in Glasgow, and there for the long period of nearly forty years he continued the practice of his art. In the earlier part of this time he formed one of a circle of talented young men, of kindred genius and humour, who often met for the interchange of wit, and the discussion of literary and artistic subjects. Of these several besides himself achieved eminence. Among them were the late Principal Leitch and his brother John, a well-known litterateur; Mr. McNish, the author of "The Anatomy of Drunkenness"; Horatio McCulloch; Norman Macleod; and Robert Macgeorge, the late genial Dean of Argyll. As years went by the circle of his acquaintances became enlarged, and he took a prominent place in the best society of Glasgow, and a warm interest in everything which concerned the interests of the city. On his election to be President of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1875, he removed to Edinburgh, and at this time he received the honour of knighthood. In 1881 the University of Glasgow conferred on him the degree of LL.D., and he received the same honour from the University of Edinburgh.

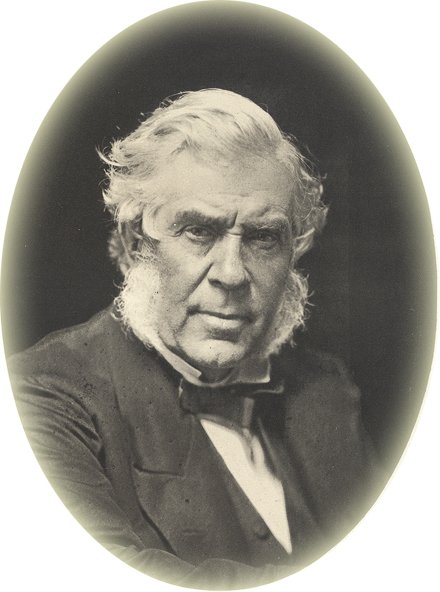

Sir Daniel was a constant exhibitor at the Royal Scottish Academy, and rarely a year passed in which he had not one or more portraits on the walls of the Royal Academy. As a portrait painter he was distinguished not more by the faithfulness of his likenesses - particularly in giving what was specially characteristic of his subjects - than by his correct colouring and the good taste and judgment shown in the treatment of his accessories. To enumerate those of his portraits which were exceptionally fine would require a long catalogue. Among those better known in Scotland are Lord Brougham in the Parliament House, Edinburgh; Lord Melville in the Archers' Hall; Dr. Norman Macleod; the Marquis of Lorne; the Duke of Buccleuch; Lord Belhaven; and others. Besides many of our Provosts, he painted a remarkably fine portrait of Mr. Robert Dalglish, M.P., one of Bailie Moir, and one of Mr. Carrick, City Architect. These three are in the Corporation Galleries. Another fine work was his portrait of Mr. Charles Randolph, painted for the University, and now in the Hunterian Museum. But of all his works none, perhaps, was finer than the portrait of Dr. Wardlaw, which was exhibited at the Great Exhibition in Paris in 1855, and for which he was awarded a gold medal there. Speaking of this picture, Dr. John Brown, in his book on Raeburn's Portraits, pronounces it equal to anything by Gainsborough. Certainly Scotland has not, since Raeburn, produced a greater portrait painter than Sir Daniel Macnee. Besides portraits in oil, Macnee, in the earlier part of his career, executed a great many likenesses in crayon. In this style of art he was unsurpassed, and some of them were exceedingly spirited and beautifully executed. The portrait of Andrew Macgeorge in this volume is from one of these chalk drawings.

Socially he was a universal favourite. He was a charming companion, and on account of his genial disposition and conversational powers his society was courted by all who came to know him. As a teller of stories he was unique, and no account of him would be complete without some notice of his wonderful powers in this respect. With an extraordinary power of mimicry, he possessed a rich fund of humour, a keen appreciation of character, and a memory amply stored with general information.

With such qualifications, and a never-failing command of language, he brought to the telling of his stories, or his delineations of character, powers of description and invention, and a richness of illustration, of the most extraordinary kind. His characters were represented to the life - their voice, their manner, their special peculiarities, even their physical appearance. And it was all done so naturally, without the slightest appearance of effort, full of fine Scotch humour, but never approaching to coarseness or vulgarity. He told the same stories often, but he never told them twice in the same way, and no matter how often his friends heard them, they found in them each time all the charms of freshness and novelty.

To tell any one of them here, as he told it would be impossible, even if space permitted; but without giving details, one characteristic example may be mentioned of his ready wit and power of invention.

It occurred about the year 1832, and the subject of it was an artist of not very high standing, but well known at that time both in Edinburgh and Glasgow. We shall call him Mr. Megilp. He was a character. He was a tall, portly man, then past middle life. He had a high opinion of his own artistic powers, and he was fond of giving advice to the younger artists, which he did in a very pompous, patronizing way. Horatio McCulloch, who was then coming into notice as a distinguished landscape painter, had invited Megilp to visit him at a house which McCulloch had taken at Hamilton; and he asked Megilp to go with him one day to Cadzow Forest to sketch. He agreed, and while McCulloch painted Megilp sat by, and in his grand way began to give him advice, and to lecture him about art, interspersing his observations with such frequent applications to a flask which McCulloch's hospitality had provided, that the lecture very soon ceased to be intelligible. McCulloch told his friend Macnee about it. As to what Megilp had said he could not tell him a word - only that he had talked a great deal of nonsense. But this was text enough for Macnee.

Megilp belonged to a club called "The Haveral," which met in a tavern behind the Register Office in Edinburgh, and which was frequented by several young artists, including Macnee and McCulloch. At one of the meetings, when Megilp was absent, Macnee happened to mention the incident in Cadzow Forest, when the artists present implored him to let them hear what Megilp had said, and this he proceeded to do. Of course, every word of it was invented at the moment, but it was done inimitably. It was Megilp himself who spoke, and the "speech" was so full of all sorts of nonsense and absurdities about art, and his style and voice and grandiose manner were so wonderfully given, that it was received by the artists with delight and shouts of laughter. So much had they enjoyed it that it came to be spoken of out of doors, and at last it came to the ears of Megilp. He was very angry, and determined to bring Macnee to account for it.

An opportunity soon offered. He came down one night to the club, and finding Macnee there, he told him what he had heard. It was true, he said, that he had been with McCulloch in the forest, and had given him his views about art, but he was not aware that he had said anything on that occasion which could provoke the indecent merriment with which, as he had been told, Macnee's account of it had been received. "And now," he said, "I insist on your repeating what you told to these gentlemen." Although thus so unexpectedly appealed to, Macnee was equal to the occasion. "Certainly, Mr. Megilp," he said, "your request is reasonable, and it cannot but be a pleasure to me to repeat what was so highly creditable to yourself." And so he went off with a disquisition on art - of its high and noble aims, of the preparatory studies necessary, and the other requisites of an artistic education.

He spoke of the mode of observing Nature and the true manner of representing it, of the qualities of colour, of light and shade, of atmospheric effects, of the principles of composition, and so on. It was all expressed in the choicest language, and conceived in the finest spirit - such a discourse, in short, as Sir Joshua Reynolds might have delivered to the students at the Royal Academy. Megilp listened to it with rapt attention, his face beaming with pleasure. But it was too much for the "artists" who were listening, and although they tried hard to look grave, the whole thing was so intensely ludicrous that more than once they gave way and broke into laughter. Megilp on these occasions looked very indignant, and once he turned to them and said in his grand way, "Hitherto, gentlemen, I have been unable to see anything to laugh at. Go on, Macnee; pray, go on." And Macnee did go on, bringing it all to a close with such a peroration as it was impossible to withstand; and nothing now could restrain the laughter, which broke out in peals long and loud. Macnee paid no attention, but turning gravely to Megilp, he expressed the hope that he had repeated with accuracy what he had said to McCulloch. "Perfectly," said Megilp, with calm dignity, and rising, he said, addressing Macnee, "these giggling idiots are unworthy of your notice or mine. I have always admired your accurate memory, Macnee, and I have reason to admire it now, for to the best of my recollection you have repeated as nearly as possible, word for word, the advice I gave to our friend McCulloch."

These two "speeches" were among the happiest examples of Macnee's wonderful powers, and they were described by those who heard them both as something never to be forgotten. It may be mentioned, in passing, that among Macnee's most characteristic portraits was one of this Mr. Megilp.

Brilliant, however, as Macnee was in society, he was even more so in his own family, or with only one or two intimate friends with them. He was very far from keeping his best stories for outside, and some of the best of them, perhaps, never went beyond the home circle. But at home or in society he was ever listened to with delight. Actors of the highest eminence heard his stories, and were unstinted in the expression of their admiration. Thackeray heard him, and pronounced him the prince of raconteurs. He was liked by all his brother artists. Even a nature so hard and ungenial as that of Turner was attracted by him, and Macnee used to say he was the only one he had ever heard of who had partaken of Turner's hospitality.

In person he was tall, with a fine massive presence, enhanced in effect by an air of old-fashioned stately courtesy in which kindliness and dignity were agreeably blended.

During most of his life Sir Daniel, as a rule, enjoyed good health, but latterly he had several severe attacks of illness which impaired his constitution. To the last, however, he continued to practise the art he loved so well, and within a few days of his death he was working in his studio. He died in his house in Edinburgh, on the 17th of January, 1882. And so there passed away in his seventy-sixth year one whom Dr. Macgregor, in preaching his funeral sermon, truly described as "one of the best known, and best liked, and most highly gifted Scotchmen of his time."

He was twice married. By his first wife, a daughter of Mr. Jardine, engineer, he had several children, of whom, all but two, a son and a daughter, predeceased him. Lady Macnee, who was his second cousin, survived him, and also one son and two daughters of the second marriage.

Back to Contents