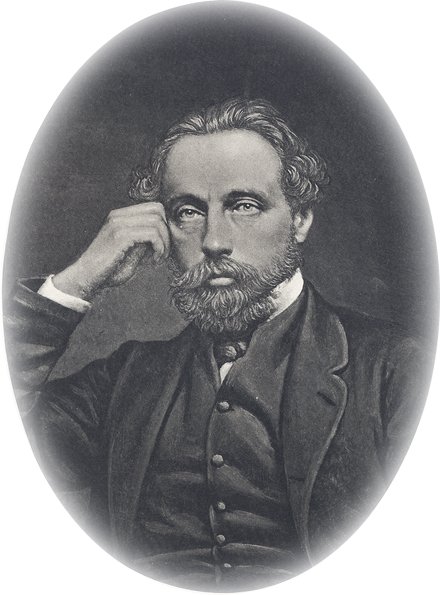

Pioneer of the Glasgow tram and bus network, Menzies was born at Balornock on 24 November 1822. The original Glasgow buses, from 1834, connected the town with the Broomielaw and Port Dundas slipways, and sedan chairs were in use elsewhere as late as 1847.

Menzies started as a woollen warehouseman, but a love of horses led to him entering into partnership, in 1846, with Thomas Mitchell, a carriage hirer and undertaker. They began operating "city omnibuses" from 1848, and soon nine buses were in operation. By 1875 Menzies had 42 buses, having established himself as the city's main operator.

The Glasgow Street Tramways Act was passed in 1869, and the Glasgow Tramway and Omnibus Company opened its lines on 19 August 1872. Menzies was managing director, but resigned shortly before his death on 19 April 1873. The company bought 500 horses and 50 buses from Menzies, along with extensive stables.

IN order to see the results of the life-work of Andrew Menzies, it is necessary only to look around in Glasgow. In our crowded streets the ceaseless stream of tram-cars runs in a channel cut for it by the energy of the man who was the first successfully to develop the omnibus system in the city, and in the suburbs the marvellous extensions of the last forty years are not less expressive of his influence; for improvements in means of conveyance stimulate the growth of cities as surely as they conduce to the development of the country at large.

It is worth while at the outset to make some observations illustrative of the conditions under which the traffic of the city was conducted about the time when Mr. Menzies was born (24th November, 1822). It will be seen that the lines upon which he in early manhood originated and carried out his omnibus system did not owe their origin to ideas which can be said to have been familiar to him during childhood. It is hard now to conceive of Glasgow without its tramways; and fifteen or twenty years ago it was hard to conceive of it without its Menzies' tartan-panelled "City buses." Yet in 1822, when Andrew Menzies was born, London even had no omnibuses, and the familiar cry of "Bank! Bank!" was as yet unuttered by the London "cad"; for it was not until nearly seven years later - namely, in July, 1829 - that Shillibeer started the first London omnibus between Paddington and the Bank of England. The omnibuses which first plied in Glasgow were those which, about 1834, began to run from the foot of Nelson Street, "to answer the sailing of the steamboats at the Broomielaw and the passage boats at Port-Dundas." Indeed, the function of omnibuses in Glasgow was for several years confined to the conveyance of passengers to and from the Broomielaw, Port-Dundas, and Port-Eglinton. Considering the throng of fast traffic of all kinds which now rushes through the streets of Glasgow, it is surprising to reflect that in 1823, the year after Andrew Menzies was born, only eight cabs or "cabriolets" - otherwise, hackney carriages drawn by one horse - were to be seen even in London. Previous to 1815, when one-horse hackneys were first licensed, all such vehicles had two horses. It does not quite appear when two-horse hackney coaches were introduced into Glasgow. They were licensed in London in 1625, and if, as Dr. Alexander Carlyle asserts, there were none in Glasgow in 1743, their existence there seventy years before that may be inferred from a burgh minute of 1673.(*) The cab, as we now know it, was preceded in Glasgow by the "Noddy" and the "Minibus," both of which were one-horse vehicles, the "Noddy" having four wheels, but the "Minibus" only two. The latter was a square box-like conveyance with the door at the back, and a deplorably rattling window on each side, and it was designed to contain two passengers, who sat facing each other in uncomfortably close proximity. Mr. W. B. Huggins, of W. B. Huggins & Co. - at one time one of the best known mercantile houses in the city - had the credit of introducing the minibus to Glasgow, he having induced some Glasgow gentlemen to join him in bringing half-a-dozen from London. Regulations issued by the Magistrates, under date 29th March, 1845, classify the "minibus" as a second-class vehicle along with the "cab," the first-class vehicles of the period being styled "Noddies," "Clarences," and "Harringtons." The "minibus" must therefore have been brought to Glasgow some time prior to the date of these regulations.

During Mr. Menzies' childhood many citizens must still have been living who could recollect the sedan chair as a means of conveyance in our city. Dr. Carlyle, speaking of it in 1743, says that in Glasgow they were then used only on rare and peculiar occasions, and that there were only three or four of them to be had; but "Senex" in his young days was familiar with them, and in 1817 there were still eighteen of them plying for hire in Glasgow. A well-known Glasgow gentleman who would justly resent being called "old," has informed the writer of this notice that he can remember sedan chairs in Glasgow perfectly. It was in a chair that his mother was in the habit of going out when invited to dinner, and his father walked alongside. This would be about 1840. There were then no cabs, and a "noddy" ordered from a post-master's office was an expensive luxury. As late as 1846 or 1847 the same gentleman remembers a dinner party given in his father's house in Blythswood Place, to which a lady came from West Regent Street in a sedan chair. This lady's husband and the narrator of the story volunteered to carry the lady home in the chair, and they ridiculed the remarks of the two porters who declared that the amateur chair-men were not able for the task. As it turned out they were able to carry their "fare" only as far as to the house of Mr. John Tennant, and then they had to give in. They had forgotten to put on the shoulder straps. The last Glasgow chair-man was an Irishman named Sweenie, who had a butter and egg shop at the east corner of Drury Street. He made money and retired to his native country, but, previous to doing so, he issued to his patrons a circular offering tickets for a raffle - prize, a sedan chair! The tickets were not taken up. Everybody was impressed with the dread of drawing the lucky number.

It is even possible that some of those who were old ladies when Mr. Menzies was a child may, in their gay days, have been escorted to the "assemblies" by William Moses, the sedan-chair proprietor, who not only assisted to carry his fair charges to the ball, but, if they could find no partners, danced with them himself. Mosesfield, the residence of this gallant chair-man, stood within a short distance of Balornock, a property which has belonged to the Menzies family for generations. It was at Balornock that Andrew was born, and there also he died.

Glasgow tolerated the comfortless hackney coaches and jolting sedan chairs until a comparatively recent period, because the bourgeoisie was content to live "in a back shop," and distances were so short that the inventive faculty was not stirred to devise means for carrying people from street to street. Haughty monopolists of Virginia tobacco or Jamaica rum lived in narrow wynds close by the shops of hecklers, on third flats of closes in Argyle Street, or in other now unpretentious places. And if they built fine mansions, the sites were chosen in the Cow-lone, or in Virginia Street or Jamaica Street, not so far from the "plainstanes " but that even in bad weather the "burgess" might reach his home with shoe buckle unsullied by the "fulyie" of the causey, and before a curl of his wig was damaged, or his scarlet cloak was more than damp. In things vehicular, there being thus no necessities, there was no invention. But invention, though born of necessity, becomes itself the parent of new necessities. So, in Glasgow, prosperity having slightly extended the suburbs, the necessities thus created gave birth to the invention of facilities for transit to and fro, and in so doing brought into existence new suburbs. It was to such important work that Andrew Menzies, perhaps unconsciously, devoted his life.

Mr. Menzies was educated in the High School, and began his business life in the service of Messrs. George Smith & Sons, whose warehouse was then in London Street. He left their employment after a time, and entered that of John Guild, "Scotch woollen warehouseman and commission agent, 113 Candleriggs." But Mr. Menzies had no liking for the work he had to do in these situations. He had more inclination towards mastering a capricious horse than towards being himself the willing serf of a capricious customer over the counter of a "soft goods" establishment. His one hobby was a love for horses. That feeling always possessed him, even while conscientiously fulfilling his duties as Mr. Guild's assistant, and the time came when it was no longer to be withstood. In 1846, when about twenty-four years of age, he entered into partnership with Mr. Thomas Mitchell, a carriage hirer and funeral undertaker, the premises of the firm being at 25 Stevenson Street, and at 14 Virginia Street, where part of the warehouse of Messrs. Mann, Byars & Co. now stands.

At the time when Andrew Menzies thus began business, there already existed a service of "City omnibuses," and there were also suburban buses which ran from Walker's Tontine Hotel to Partick and to Rutherglen, and from 91 Trongate to Port-Dundas. About this same time, also, Wylie & Lochhead began to run a bus four times daily to the Botanic Gardens. The service of "City omnibuses" had been originated by Robert Frame, a reporter on the staff of the "Reformers' Gazette," who, on 1st January, 1845, started a bus from Barrowfield Toll, Bridgeton, to the "Gushet House," Anderston, fare twopence all the way. The projector of the venture acted as his own guard, and he must have been somewhat discouraged to find that the crowds of New-Year's Day pleasure-seekers in the streets contented themselves at first with staring at the vehicle without patronizing it. Not a single passenger entered it on the first trip over the whole distance of two miles, but on the return journey curiosity began to work, and the omnibus was filled. As the day advanced patronage increased, but unfortunately the strength of the conveyance was not equal to the weight of the traffic; the side panels burst, and no more passengers could be carried that day. On the following morning, however, Frame took the road with an old stage-coach, covered with bills describing it as "Frame's City Omnibus - Bridgeton and Anderston - Fare Twopence," and this nondescript conveyance ran till the wrecked omnibus was repaired. As the traffic developed, Frame added new runs, and in the spring of 1846 he had four omnibuses and forty horses employed. But 1846 was the year of the potato blight, with all its consequences of dear grain and universal distress. The working classes, for the relief of whom soup kitchens had to be instituted, were barely able to subsist, and could not afford to ride in omnibuses, so that Frame's traffic fell off at the very time when the cost of feeding his horses seriously increased. As a consequence his enterprise totally collapsed in 1847. Frame became bankrupt, and his stock and plant were sold off. After this he obtained the appointment of inspector of carriages plying for hire in Glasgow, and he now holds the post of officer in charge of Bridgeton Police and Fire Station in the Old Dalmarnock Road. Frame, besides directing his attention to the utilization of horses of an earthly breed, was bold enough to take an occasional mount upon Pegasus even, and to climb with his aid into the ethereal realms of poesy. The result of these excursions appeared in a volume of verses which was printed and published.

For several months after the collapse of Frame's scheme, Glasgow was without "City omnibuses," and it almost appeared as though enterprise in that direction had received a permanent check. In the autumn of 1848, however, a firm called Forsyth & Braig began to run a bus over Frame's old route, and shortly afterwards Mitchell & Menzies started that line of "City omnibuses," which became one of the most successful institutions of Glasgow. The success attained is entirely attributable to the energy, tact, and enterprise of Mr. Menzies; for Mr. Mitchell very soon retired from the copartnery - some time in 1850 or 1851 - and left Mr. Menzies unfettered in his action, which was always prompt, bold, and unhesitating. The pulse of the public having first been carefully felt, Mr. Menzies showed no delay or half-heartedness in following the indications of its beat. Already, in February, 1850, he had two buses running between Bridgeton and Anderston, two between Bridgeton and Cowcaddens, two between Whitevale and Cowcaddens, and three between the Cross and Anderston - nine omnibuses in all. On 22nd April, 1850, the "Bridgeton and Crescent" route was opened, and buses were put upon the "Port-Eglinton and Crescents" line on the 18th of the following month. The fare upon all these routes, except that between the Cross and Anderston, was twopence all the way, the distances averaging from 2½ to 2¾ miles. Between the Cross and Anderston the fare was only one penny, and the line along the busy thoroughfare connecting these two points was always dealt with as the chief of the "City omnibus" series. At first the omnibuses upon it ran at intervals of ten minutes, which, as traffic developed, were shortened to seven and a half, then five, then three, and lastly, in 1875, the "Anderston and Cross" buses ran every two minutes and a half. In that same year Mr. Menzies had 35 omnibuses constantly employed upon what might be called the "City" routes, besides one bus to Shawlands, three to Springburn, and three to Pollokshaws and Thornliebank - 42 in all. Of course so much success proved an incentive to opposition. Some time late in 1849, or early in 1850, a bus was started between Royal Crescent and Whitevale by Wm. Cowan, and a year or two afterwards Jas. Hutcheson and a person named Craig attempted to compete upon the Bridgeton and Cross and Cross and Anderston routes. All had, however, to succumb to Andrew Menzies. Indeed, the public feeling of the time is well represented in a paragraph which appeared in the "Glasgow Examiner" of 8th February, 1851, a propos of competition from a more formidable quarter. "The suburban buses," it says, "are all fair game, but the citizens will acknowledge no city omnibuses but those of Andrew Menzies." They were the largest, handsomest, and most comfortable buses in the kingdom; they were drawn by three horses abreast instead of the ordinary two; and they were supplied with a patent foot drag invented by Mr. Menzies, besides being under the control of civil and smartly-dressed guards, who started and stopped the buses by means of a bell-signal, which obviated shouting - the only means of signalling in vogue up to that time. The only serious competition which the City omnibuses ever encountered was from those started by Duncan MacGregor; but the prosperity of Mr. Menzies' undertaking was in no way affected thereby.

For another of his successful schemes Mr. Menzies deserves to be gratefully remembered by many a holiday-seeker. He was the chief promoter and took an active share in the management of the Highland coaches which ran through the far-famed Glens Coe and Orchy, and between Loch Lomond and Oban by way of Tyndrum, Dalmally, and Loch Awe. What a host of delightful associations are awakened by the names of these places; what recollections of many scrambles for box seats and many pleasant rides upon these coaches - now, alas, no longer in existence; for the Oban Railway and the lake steamers have swept most of them away.

While Mr. Menzies' omnibus system was maturing, tramways began to attract attention. Although the failure of the first one opened for the New York and Haarlem Street Railway in 1832 damped the ardour of promoters for twenty years, tramways were again revived in America in 1852 by Lougat, a Frenchman, who laid lines in New York. In 1857 tramways were introduced to British notice by the redoubtable George Francis Train, who attempted, with the assistance of Mr. James Samuel, C.E., to introduce them into London. Train and Samuel applied in 1858 for an Act, but Sir Benjamin Hall, the Chief Commissioner of Works, opposed and got it thrown out. In March, 1860, however, Train applied for and obtained local permission to lay lines in Birkenhead, and having patented his system, he in 1861 laid the first London tramways in Bayswater Road, as well as between the Marble Arch and Nottinghill, Westminster and Kennington Road. In 1863 further lines were laid in the Potteries district; but after a brief experience Train's system of rails was found to interfere with the ordinary traffic, and all the London lines were taken up.

In November, 1865, a new rail having been invented, a trial-line was laid in Castle Street, Liverpool, but it shared the fate of the other pioneer lines and was removed some four years afterwards. At length, application having in 1866 and 1867 been made to Parliament for power to lay tramways in Liverpool, an Act was obtained, and Liverpool acquired in 1868 the distinction of possessing the first authorized tramway line laid in England. At this time the word "tramway" had no place in the standing orders of the House of Commons, and the promoters of the Liverpool tramways had to apply under the standing orders applicable to railways. Another year expired before tramways were authorized in London, and laid by the North Metropolitan Company on the Whitechapel, Mile-end, and Bow Road. In the succeeding year the "Glasgow Street Tramways Act" was passed, and under certain arrangements between the British and Foreign Tramway Company (Limited), the Corporation of Glasgow, and the Glasgow Tramway and Omnibus Company (Limited), the prospectus of the latter company was issued on 21st November, 1871. The line was opened for traffic upon 19th August, 1872. Mr. Menzies was chosen as managing director for five years.(**) This appointment, however, he resigned in the spring of 1873. The company acquired from Mr. Menzies 500 horses and 50 omnibuses and extensive stables in Risk Street and North Street; but Mr. Menzies retained his business as postmaster and funeral undertaker, and he opened premises for carrying it on at 110 to 126 St. George's Road. This concern was shortly after Mr. Menzies' death acquired, and it still is conducted, by his cousin, Mr. Alex. Davidson, who had been associated with him in the business since 1857.

Some notion of the magnitude and possibilities of the undertaking which Mr. Menzies was the first to carry on with permanent success may be gathered from the following facts. When he made his sale to the Tramway Company, it may be calculated that the purely "City buses" ran between 2,000 and 3,000 miles per day in the streets of Glasgow. Now the tramway car system is rapidly approaching, if it has not already reached, that point of perfection which, in the opinion of experts, is gained when a car is always in sight. At 31st December, 1883, the Tramway Company possessed 2,366 horses and mules, 233 cars, and 24 omnibuses, which ran 1,926,124 miles during the half-year, or, on an average, 12,268 miles per day. During the half-year which ended on the above date the Company carried upwards of 800,000 passengers per week, or over 40,000,000 per annum, and earned a gross revenue in the half-year of £107,032, being at the rate of £214,000 per annum. This shows "the power of the penny."

Mr. Menzies' father died suddenly of heart disease when Andrew was six or seven years of age, and the impression made by the event working upon his young mind may have produced the presentiment, which he undoubtedly had, that he himself should die suddenly. The presentiment proved to be well founded. On Saturday, 19th April, 1873, he attended business, in the evening he complained of indisposition, and shortly after breathed his last. Mr. Menzies married on 16th April, 1849, Mary, youngest daughter of the late David Buchanan, farmer, East Muckeroft, near Chryston. Mrs. Menzies died on Christmas-Day, 1882.

Although more than once feted at public banquets (Sir Archibald Alison being chairman on one of these occasions), Mr. Menzies did not pose as a public man. If congratulated upon the importance of his omnibus system as an institution of his native city, he would probably have replied that his main motive in business was his love for horses - not a sentimental notion, but a strong practical desire to develop their usefulness to man. One of Mr. Menzies' fixed theories was that any horse which required veterinary attendance for more than three consecutive months ought to be destroyed; and destroyed accordingly were all such cumberers of his stables. A true benevolence underlay this seemingly harsh and peremptory treatment, as any one will recognize who considers the ill-usage and misery in store for maimed or unsound horses which are parted with because of their infirmities. Indeed, this practice of Mr. Menzies indicates several of the most marked traits of his character: his firmness aiding him to carry out what his prudence and good-heartedness indicated as the best course. To those who knew him least, the benevolence and kindliness of his disposition were partly concealed by the reticence of his demeanour, but his good qualities were nevertheless displayed in many unmistakeable forms. Amongst these may be mentioned the deep interest he took in the business of the Barony Parochial Board, of which he was chairman, during the four years preceding his death, he having had the exceptional honour of being elected chairman of the Board for five years in succession. He was the moving spirit in the introduction of many important measures for the benefit of the parish. On 17th November, 1871, he cut the first sod of the ground whereon Woodilee Asylum now stands, and on 4th October, 1872, he laid the foundation stone of the Asylum Buildings. A life-size bust of Mr. Menzies stands in the chief corridor of the Asylum as a tribute to his memory. Mr. Menzies' acts of private kindness, too, were numerous. One which was highly characteristic may be cited as an example. Learning that Mr. Walker, his opponent in trade, was seriously indisposed, he volunteered his services, and for a considerable period managed that gentleman's business along with his own. The reticence which somewhat limited the circle of his personal friends was but the indication of a nature which preferred deeds to words.

(*) "Glasgow Memorabilia," page 216; 1868 ed.

Back to Contents