Born in Edinburgh on 6 February 1806, Ramsay earned the highest honours in Latin, Greek and mathematics at Glasgow College before taking up residence at Trinity College, Cambridge in October 1825. He again topped his class in 1826 and 1827 before his health failed and he was unable to gain honours in the mathematical tripos.

In 1829 he was asked to provide cover - due to illness - for the chair of mathematics at Glasgow University. In 1831 he was appointed to the chair of humanity, a post which he held until retirement in 1863. His published work included a "Manual of Latin Prosody" (1838; enlarged and rewritten in 1859) and a "Manual of Antiquities" (1851). He also contributed to Smith's "Dictionary of Antiquities".

He was one of the first amateur photographers, and a successful farmer. He died at San Remo on 12 February 1865.

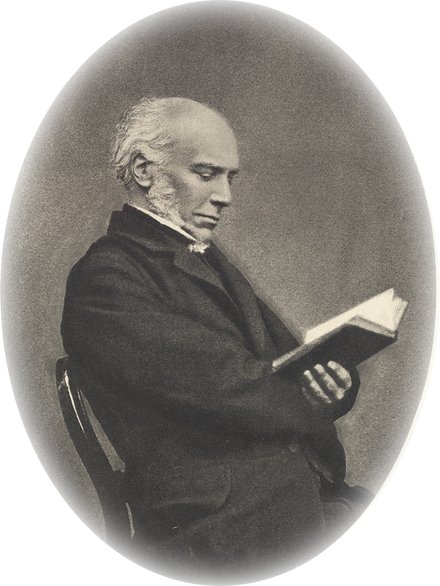

AMONGST the many notable teachers who have left their mark upon the Universities of Scotland during the present century, a conspicuous and in some respects a unique place must be assigned to William Ramsay, who from 1831 to 1863 held the Professorship of Humanity in the University of Glasgow. As Glasgow was the scene of all his professional life, and as he possessed a combination of qualities which made him no less eminent as a citizen than as a scholar, he fitly holds a place amongst those whose memory our city would keep alive.

William Ramsay was born in Edinburgh upon the 6th February, 1806. He was the third and youngest son of Sir William Ramsay, seventh baronet of Bamff, in the county of Perth. Brought up under the superintendence of a careful and judicious mother, he received his first education in the High School of Edinburgh, during the Rectorship of Professor Pillans. He thence passed on to Glasgow College, where he spent two sessions under the roof of Dr. Chrystal, who was at that time head of the Glasgow Grammar School, and whose family ever afterwards felt the warmest affection for him. During his student career he formed a friendship which greatly influenced his life with the distinguished Greek Professor, Sir Daniel K. Sandford, a friendship which remained unbroken until the early death of the latter in 1837. Having won the highest honours in the Latin, Greek, and Mathematical Classes, he commenced residence at Trinity College, Cambridge, in October, 1825. In the College Examinations of 1826 and 1827 he obtained the distinction of being first in the First Class - a position which, according to the scheme of examination then in vogue, implied equal proficiency in classics and in mathematics. In his third year his health broke down, and he was thus unable to present himself for honours in the mathematical tripos.

Meanwhile the Glasgow Professors had not lost sight of him. In 1829 Professor Millar, the occupant of the mathematical chair, became incapacitated, and Mr. Ramsay was appointed to act as his substitute. For two years he conducted the whole work of the mathematical chair. He at once restored order into a disorganized class, and the excellence of his teaching in that subject is recorded in the statement of a senior wrangler who was among his pupils - the late Mr. A. Smith of Jordanhill - that he never throughout his life forgot any demonstration which he had learnt from Mr. Ramsay. In 1831 he was appointed to the Chair of Humanity upon the death of Professor Walker, a post which he filled until his retirement in 1863. He died at San Remo on February 12, 1865.

Few teachers have ever left upon their pupils - of whatever class or type of mind - so deep and clearly-cut an impress of their personality as Professor William Ramsay. Generations of students still remember the erect figure, the clear, lively voice, and the animated action, which commanded attention and filled the dullest work with life; the inexorable light-blue eye which was the despair of the inattentive; the ready jest, the kindly humour, which lighted up the hour; the sympathy which encouraged the timid but honest worker, the incisive sarcasm, or, if need were, the crushing rebuke, which extinguished idleness and presumption.

Great as was his skill in class management, it was no less great in the directing of his teaching to meet the special wants of his class. Himself an exact as well as a learned scholar, intolerant of inaccuracy, he made it his first object to secure thoroughness and scrupulous accuracy of knowledge: being also an accomplished man of the world, full of human sympathies and interests, and a stranger to all pedantry, he put the substance as well as the form of the great Latin writers before his class, and clothing the past with all the life and richness of the present, he used it as a great implement of humane instruction, and touched the minds of his hearers with an interest in all the deeper problems of life and literature.

Professor Ramsay was author of several important works, which placed him in the first rank among British scholars. In 1833 he published a remodelled edition of Hutton's "Course of Mathematics"; in 1838, a "Manual of Latin Prosody," enlarged and rewritten in 1859. In 1851 he published his well-known "Manual of Antiquities," and in 1838 he edited the "Pro Cluentio" of Cicero. In addition he contributed some of the most important articles to Smith's "Dictionary of Antiquities," amongst which the articles on "Cicero" and on "Roman Agriculture" stand pre-eminent. An edition of Plautus was unfortunately left incomplete at his death. These writings display, both in matter and manner, the same qualities which marked the man. Exactness of knowledge, candour and acuteness of judgment, vigour, animation, and an unaffected purity of style, mark them all.

Few teachers have been more abundantly rewarded than he was by the respect and affection of his old students. The interest which he never failed to take in their fortunes was returned in many a life-long friendship. One of the most distinguished of these has written that "it would be difficult to exaggerate the debt which Scotland owes to him as one of the best classical teachers whom she has ever produced, and as one of the few men who in this century have by their writings succeeded in vindicating her claims to scholarship."

Professor Ramsay was an excellent man of business. He took a leading part in all college work, and for many years managed the whole finance of the University, almost unaided. "His strong sober judgment, his insight and power of decision, his courtesy and self-command and kindliness" - so writes a colleague of twenty-six years' standing - "witnessed by the members of the Senate for upwards of thirty years, made the whole body feel his resignation rather as the loss of a dear friend and invaluable helpmate than as the retirement of an ordinary colleague."

When we add that he had a considerable practical knowledge of chemistry, and was one of the first amateurs to practise photography in this country; that he was an authority upon ancient coins; that he was a successful practical farmer; that for many years of his life he was an ardent sportsman and an excellent shot; and that to those old pupils and others who knew him intimately, and were welcomed to the kindly hospitality of his country home at Rannagulzion, the charm of his social qualities outweighed all the other claims upon their regard - enough has been said to justify his being placed among a list of citizens of whom Glasgow has reason to be proud.

Back to Contents