The son of an eminent physician, Towers (as he was originally known) was educated in Glasgow and pursued a career in law. He moved to Edinburgh in 1826 but returned to Glasgow in 1829 and entered the Faculty of Procurators. Business was slow until 1832, when he accepted a partnership with Robert Reid and came into demand for his expertise in conveyancing and mercantile law.

Despite coming from a staunch Tory family, Towers was active in the Whig cause at the time of the Reform Bill. In 1859 his cousin William Clark, founder of the Free Church College of Glasgow, bequeathed him his estate of Wester Moffat, along with a substantial fortune, on condition that he took the surname Clark.

In 1867 he was unanimously elected dean of the Faculty of Procurators. He died suddenly on 23 April 1870, and was buried in the old churchyard at Shotts.

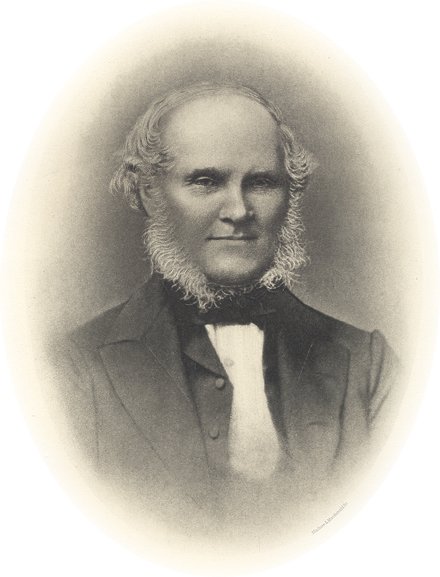

MR. TOWERS (afterwards Towers-Clark) was born in 1805, and was the youngest son of Mr. James Towers, long one of our most eminent physicians, and from 1815 down to his death in 1820, one of the professors in the Medical Faculty of the University of Glasgow.

At the age of ten he entered the Grammar School of Glasgow, the class which he joined being under the charge of Dr. John Dymock, a gentleman of very great classical attainments, an excellent teacher, and also a strict disciplinarian, as numbers of his more recent pupils, who are still living, can well testify. After the usual four years at this school, in which he took a very high place, being in one of the years the dux of his class, Mr. Towers was sent to the University of Glasgow, and he attended in regular succession all the classes in the Faculty of Arts except that of Natural Philosophy.

We may be allowed to make a passing reference to one of the classes in the Faculty of Arts - that of Logic - the more especially as Mr. Towers entertained a very grateful recollection of the benefit which he had derived from the teaching of the professor. At the date of which we speak the Chair of Logic was filled, as indeed it had been filled since 1787, by George Jardine of Hallside, Cambuslang, a gentleman whose only published work is "Outlines of a Philosophical Education," but whose success as a teacher brought students to Glasgow from all parts of the empire. That success was not owing to any very great merit in his prelections, for, if we may judge from the opinion pronounced by Whately after perusing the "Outlines," these prelections were not in any way remarkable; it was owing to the marvellous power which the professor possessed, not only of enlisting the attention at the outset, and of keeping it enchained, as it were, during the entirety of the session, but of what we may term bringing out the student; in other words, of teaching him both to think for himself and to rely on himself. This worthy man retired from the active duties of his chair in 1824, to be succeeded, in 1827, by his favourite pupil and assistant, the late Robert Buchanan, who, as a teacher, followed in the footsteps of his master and predecessor, and left a name the remembrance of which is still cherished by many thousands of men scattered over the globe - merchants, divines, lawyers, and physicians.

Having chosen the profession of the law, Mr. Towers was, in 1821, and while still attending the Arts classes, apprenticed to his cousin, Mr. Adam Graham, writer, then a partner of the firm of Hill Graham & Davidson, now represented by the house of Hill Davidson & Hoggan.

During the latter portion of his apprenticeship he attended the prelections of Mr. Robert Davidson, advocate, who, some twenty years before, had been called to the Chair of Civil and Scots Law, so long and so successfully filled by Professor John Millar.

In 1826 he removed to Edinburgh, and accepted a situation in the chambers of Messrs. Inglis & Donald, W.S., with the two-fold object of acquiring a knowledge of Court of Session practice, and of attending the lectures of George Joseph Bell on Scots Law, and of Macvey Napier on Conveyancing.

Returning to Glasgow in 1829 he at once entered the Faculty of Procurators, and began to practise on his own account. Business, however, did not flow in upon him as rapidly as he could have wished, and indeed had expected, and so disheartened was he after a trial of three years that, for a short time, he actually entertained the idea of quitting the profession, and of betaking himself to some other kind of business in which he might hope to attain success.

Hitherto he had practised alone, but in 1832 a partnership was offered to him, and he gladly availed himself of it. In that year the business which had been founded by Mr. Nathaniel Stevenson of Braidwood in 1796, and from which that venerable gentleman had retired in 1827 to enjoy in the Upper Ward of Lanarkshire his well earned leisure, was being carried on by Mr. Robert Reid, a former and favourite apprentice, and by a kinsman of his own, Mr. John Harvie, under the firm of Reid & Harvie, when, in consequence of the death of a near relative, Mr. Harvie succeeded to the entailed estate of Quarter, in Stirlingshire. Availing himself of this accession of fortune, Mr. Harvie (thereafter Mr. Harvie-Brown) resolved to quit the profession, for which, as he frequently avowed, he never had any liking; and thereupon he introduced his friend Mr. Towers; the introduction being followed by a partnership under the firm of Reid & Towers, now represented by that of Roberton Low Roberton & Cross.

We must now revert to an earlier portion of Mr. Towers's history.

As his father was a Tory, and a staunch supporter of the old system of things, it might naturally have been expected that Mr. Towers would have been opposed to the many efforts that were being made during the reign of George the Fourth to effect a change in our system of parliamentary representation. But the case was far otherwise, for no sooner had he returned from Edinburgh than he threw himself heart and soul into the great struggle for a change. Prior to the Act of 1832 all questions relating to the qualification for the county franchise had to be settled by the Court of Session, and they were fought with intense keenness, nay bitterness, and invariably at vast expense. But by the Act a much more simple and certainly a much less expensive mode of dealing with the matter was introduced - we refer to what were termed Registration Courts, in which the Sheriffs of the counties were empowered to act as judges. Thereafter these courts became the great scenes of contention for political influence - the effort of each party being to get as many of their own men as possible put upon the register, and not only so, but to exclude or disqualify as many of their opponents as possible. A great field was thus opened up for the display of legal acumen and debating power, and Mr. Towers was at once selected by the Whig party to do battle for them in the Registration Courts, not only as concerned Glasgow, but also as concerned Lanarkshire, and some of the adjoining counties, more especially the county of Stirling. A more fitting person for the arduous task could not possibly have been found, for with the energy of youth there were combined an extraordinary power of application, a thorough knowledge of the forms of court, a disposition to master the minutest details, a minute acquaintance with the principles of feudal conveyancing, and a masterly skill in applying them, a remarkable power of separating what was of primary from what was merely of secondary importance, great skill in presenting the strong or salient points of his own case, and equally great skill in detecting and exposing the weak points in the case of his adversary, and finally great fluency and readiness as a debater. His chief opponent in these contests, which lasted for upwards of ten or twelve years, was the late Mr. Robert Lamond, a gentleman, who, had he gone to the metropolitan, instead of to a merely local bar, such as that of Glasgow, would have taken very high rank as a counsel, for besides being an excellent lawyer, and possessed of great tact and judgment, he was an admirable speaker, not only fluent and graceful, but also concise and thoroughly practical.

Mr. Towers took a very active part in the contest of 1837, when Lord William Bentinck, who had shortly before returned from the Governor-Generalship of India, was returned as one of the two members for Glasgow; again, in 1847, when what was known as "The Clique," represented by the late Mr. John Dennistoun and the late Mr. Dixon of Govanhill, was defeated by the return of Mr. Hastie and Mr. John McGregor; and again, in 1852, when these two gentlemen were returned in opposition to Viscount Melgund, now Earl of Minto, and the late Mr. Peter Blackburn, afterwards M.P. for the county of Stirling, and one of the Lords of the Treasury in Lord Derby's first administration.

By way of showing how generously Mr. Towers gave himself to the struggle, we may mention that from first to last, whether in registration contests or in the parliamentary contests for the city or for any of the counties, his services were rendered entirely gratuitously.

It must not be supposed, however, that amid the excitement of politics Mr. Towers was unmindful of general business. On the contrary, in connection with that kind of business he was as eager for success as he had been for political victory; and as his aptitude for it had been manifesting itself for many years, he at last found himself in constant and extensive employment, and this, too, both in the department of conveyancing and in that of mercantile law.

We have spoken of Mr. Towers as a lawyer. We must now say a few words of his acquirements in some other departments in which, generally speaking, neither advocates nor solicitors possess any great amount of knowledge. From 1832 downwards he had been extensively employed in questions regarding the erection of iron-founding and engineering premises, with this result, that he was perfectly familiar with the details of these businesses - with what were eligible sites, with the cost of the necessary erections, with the kind and the cost of the plant required, and with all the necessary financial arrangements. Then as regards ordinary buildings, whether private dwelling-houses or tenements of land - here he was as familiar with every necessary detail, however minute it might be, as if instead of being bred to the law he had been brought up as a builder or as a joiner. Again, if the question intrusted to him related to shipbuilding, or to the construction of a dock or a canal, he was as much at home with the whole matter, and as thoroughly able to deal with it, as if he had served a long and diligent apprenticeship with, in the one case, a first-class shipbuilder, and, in the other, with a leading civil engineer. It will readily be imagined what an immense advantage this very peculiar and varied experience and information gave him in every question involving any of the matters of which we have just spoken. The truth is that many an able and experienced professional witness who had been brought forward to give what is called skilled evidence before the court or before an arbiter, lived to confess that all his testimony had been completely broken down, and had gone for nothing, under the cross-examination to which Mr. Towers had subjected him; nay more, that the examination had been the closest, the most practical, and the most severe, to which he had ever been subjected.

His zeal for his clients might be said to be unbounded, and knowing as they did how carefully he attended to their interests and how earnestly and skilfully he fought for them, they rewarded him with their confidence and their friendship.

In 1859, and when he had attained a prominent position in the very front rank of the profession, his cousin, Dr. William Clark, the well-known founder and endower of the Free Church College of Glasgow, bequeathed to him his estate of Wester Moffat, and the whole remainder of his property of every kind, coupled with an injunction to bear the surname of Clark. Mr. Towers therefore became, and to his death continued, Mr. Towers-Clark. This accession to fortune was known to be great, nevertheless it did not wean him from the profession. On the contrary, he continued to attend to business, not, however, to the same extent as formerly, for the details connected with the management of his own private means, and of the fortune which his kinsman had bequeathed to him, necessarily engrossed a very considerable share of his time and attention.

In 1867, and upon the resignation of his friend Mr. (afterwards Dr.) James Mitchell through ill health, Mr. Towers-Clark was unanimously elected Dean of the Faculty of Procurators. This honour was highly gratifying to him.

After 1857 he took no prominent part in the contests for the representation of Glasgow; but he was warmly interested in the general election of 1865, and particularly in the contest for Stirlingshire, which resulted in the return of Admiral Erskine. He was also a vigorous and influential supporter of Sir Edward Colebrooke in his various contests for the northern division of Lanarkshire, and of Mr. Hamilton of Dalzell in his various contests for the southern division of that County.

We should mention that he left the Established Church at the Disruption in 1843, and that he was an active and liberal supporter of the Free Church down to the date of his decease.

Mr. Towers-Clark died very suddenly of heart disease on 23rd April, 1870, just as he had attained his sixty-fifth year; and his remains now rest in the ancient churchyard of Shotts, in the same tomb in which repose many generations of the family whose representative he became in 1859 - the Clarks of Wester Moffat.

Back to Contents