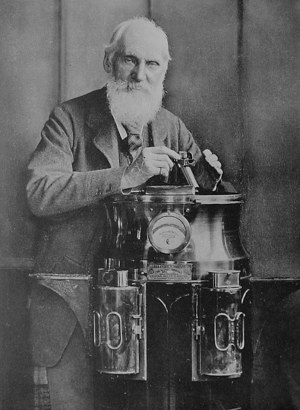

RIGHT

HON. LORD KELVIN

RIGHT

HON. LORD KELVINAFTER a long life of unwearied industry and unrivalled achievement, Lord Kelvin stands to-day in a place of universal honour, unquestionably the greatest and most revered man of science of our time. His grandfather was a Scottish Ulsterman, tenant of a small farm at Annaghmore, Ballinahinch, County Down. His father, James Thomson, born there in 1786, intended first to become a Presbyterian minister, and studied at Glasgow University. But after taking his degree in 1812 he accepted an appointment as teacher in Belfast Royal Academical Institution, and became Professor of Mathematics when the collegiate department was added to that school. He received the degree of LL.D. from Glasgow University in 1829, and three years later was appointed Professor of Mathematics in the old College in High Street. Among the many books which he wrote, memoirs and text-books, Thomson's Arithmetic was in universal use for generations, and remains justly famous to the present day. He died 12th January, 1849. Of his sons two became professors in the University of Glasgow.

William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, was born at Belfast 26th June, 1824. Eight years later he removed with the family to Glasgow, and at the age of ten, along with his brother James, matriculated at Glasgow University Seven years later he went to St. Peter's College Cambridge, and in 1845 not only took his degree as Second Wrangler, but came out as first Smith's prizeman. He was twice subsequently elected a Fellow of his college. After taking his degree he went to Paris, and wrought for a time in the laboratory of Regnault, at that time working out his problems regarding unknown properties of steam. In 1846, when no more than twenty-two years of age, he was offered, and accepted, the Chair of Natural Philosophy in the University of Glasgow. That chair he occupied for fifty-three years. During that period he never ceased to make contributions of the utmost value to the work and progress of the world, but the achievement which appealed most strongly to the popular mind commenced in 1856. The first attempts were made to lay a telegraph cable across the Atlantic in 1857, but they failed. The dramatic moment arrived on the 5th of August, 1858, when a temporary success was achieved. The first few messages flashed from continent to continent, and were read on Professor Thomson's mirror galvanometer. There were great rejoicings everywhere; but gradually the signals became fainter, and then ceased. During the next seven years preparations for making and laying a stronger cable were perseveringly worked out; Professor Thomson also greatly improved his instruments for testing cables and signalling through them. In 1865 another attempt was made, which failed through the cable breaking in mid-ocean. Professor Thomson, in a communication to the Royal Society of Edinburgh, gave reasons, founded on dynamical theory, for confidently believing that a well planned effort to lift the broken end from the bottom of the sea, in water two miles deep, would be successful. The effort was made in 1866, when, after the laying of a first complete cable successfully across the Atlantic from Ireland to Newfoundland, the broken end of the 1865 cable was lifted and joined to a fresh cable on board the Great Eastern, and a second line across the Atlantic was completed. For his great work in connection with the cable Professor Thomson received the honour of knighthood. Twenty-six years later, in 1892, he was raised to the peerage with the title of Baron Kelvin of Largs.

Meanwhile he continued to produce invention after invention. His name is

identified especially with electric and magnetic instruments, but nothing has

been beneath his notice, from improvements in water-taps upwards, and perhaps

his best-known inventions are his wonderful deep-sea sounding apparatus and the

improved mariner's compass now in universal use. He was one of the engineers for

the French Atlantic Cable in 1869, the Brazilian and River Plate Cable in 1873,

the West Indian Cable in 1875, and the Mackay-Bennett Atlantic Cable in 1879. In

1890 he was chairman of the International Commission which reported on plans of

generating and transmitting power from Niagara Falls. And his house at Glasgow

University was the first in Britain to be lit with incandescent electric lamps.

Meanwhile he continued to produce invention after invention. His name is

identified especially with electric and magnetic instruments, but nothing has

been beneath his notice, from improvements in water-taps upwards, and perhaps

his best-known inventions are his wonderful deep-sea sounding apparatus and the

improved mariner's compass now in universal use. He was one of the engineers for

the French Atlantic Cable in 1869, the Brazilian and River Plate Cable in 1873,

the West Indian Cable in 1875, and the Mackay-Bennett Atlantic Cable in 1879. In

1890 he was chairman of the International Commission which reported on plans of

generating and transmitting power from Niagara Falls. And his house at Glasgow

University was the first in Britain to be lit with incandescent electric lamps.Among his other undertakings, Lord Kelvin was engaged as a witness before many commissions and in numerous legal cases, in which his vast attainments of scientific knowledge set his evidence beyond all question. Honours and degrees were lavished upon him from all quarters of the world, and on the occasion of the jubilee of his professorship in 1896, there was a three days' festival at Glasgow University such as had never been known in scientific annals before. The two thousand five hundred guests received by the Senate included all the most brilliant and best-known men of science living in the old world and the new. Upon that occasion a telegram was sent from the library of the University which, after passing through Newfoundland, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Florida, and Washington, travelling 20,000 miles and traversing the Atlantic twice, was received by Lord Kelvin seven and a half minutes after its despatch. Nothing perhaps could better show the affection with which the veteran of science was universally regarded than the world-wide expressions of anxiety with which the news of his serious illness in 1905 was received. Among his honours he was a Deputy Lieutenant for Lanarkshire, a member of the Prussian Order of Merit, a Grand Officer of the French Legion of Honour, a Commander of the Belgian Order of King Leopold, a Foreign Associate of the French Academy, and a Foreign Member of the Berlin Academy of Science. He was President of the British Association in 1871, President of the Royal Society from 1890 to 1895, and five times President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 1904 Glasgow University paid him the highest honour in its power by electing him its Chancellor. Throughout his life Lord Kelvin continued to make important contributions to scientific literature. From 1846 to 1853 he edited the Cambridge Mathematical Journal, and for twenty-five years he was editor of the Philosophical Magazine, while among his larger works are his Baltimore Lectures on "The Wave Theory of Light," and, in collaboration with Professor Tait, of Edinburgh, the celebrated two volumes, "Treatise on Natural Philosophy," published in 1867, and the "Elements of Natural Philosophy," published in 1872.

Unlike most men of science, Lord Kelvin was not unmindful of the calls of citizenship. On the promulgation of Mr. Gladstone's Home Rule Bill he threw himself, as a native of the North of Ireland, into the political arena, and by the weight of his opinion and argument helped largely the defeat of that measure.

His Lordship married, first, in 1852, Margaret, daughter of Walter Crum, of Thornliebank. She died in 1870, and in 1874 he married Frances-Anne, daughter of Charles R. Blandy, of Madeira, who survives him. After an illness of three weeks Lord Kelvin died at his residence, Netherhall, Largs, on Tuesday, 17th December, 1907, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey.